*Author’s Note: This entry was originally published as a standalone script analysis, but has since been rebranded as part of the Five Faves series. Enjoy!*

This weekend brings Avengers: Infinity War to theaters, a much-anticipated superhero extravaganza sure to rake in an embarrassing amount of money. I’ve never really bought into the superhero movies craze, finding most of them bloated and unnecessary, but I can appreciate when the good ones come around (usually once a year or so). This year’s Black Panther and last year’s Logan, for instance, are both excellent standalone films with strong screenplays that could exist separate from their larger universes and still be worthy of merit. In honor of comic book movies’ big weekend, I want to dig deeper into the greatest superhero film ever made, Christopher Nolan’s masterpiece The Dark Knight (2008), and examine why it works so well.

Where screenwriters Jonathan and Christopher Nolan succeed while others fail is in crafting their characters first and worrying about set pieces after. This is less of an action-adventure piece than a crime drama, with conflicting viewpoints on humanity and morality coming into direct contact, manifested in Batman and the Joker.

(Note: I strongly recommend watching Lessons from the Screenplay’s video essay on the film for more on why its story and characters work so well. I will mostly be adding onto and expanding upon his ideas.)

The Flawed Hero

My primary issue with the protagonists of most superhero films is twofold. One, most superheroes are too unwavering in their resolve and remain more or less the same throughout the entire runtime. Their character arc is defined entirely by their conflict, and the decisions they make do not force them to change as people. And two, the protagonist is never in any real danger; when you know as a viewer that the studio would never allow our hero to get seriously injured or killed, the stakes are always low. No matter how ridiculous and over-the-top the danger they get into is, you know deep down that they’ll get out of it somehow.

The Dark Knight is special because neither of those two things prove true. Bruce Wayne is a troubled man, perpetually unsure if his approach to crime-fighting is the most effective. His battle with the Joker is as much a battle with himself, as his moral codes and convictions are constantly called into question. Furthermore, we never feel like Batman is unstoppable: from the first battle sequence we see just how mortal he is. Dogs give him fits, bullets still affect him, and his body is starting to grow black and blue. Even in the simplest of conflicts we fear for Batman’s safety…we don’t need entire planets or galaxies to hang in the balance for us to care about the stakes.

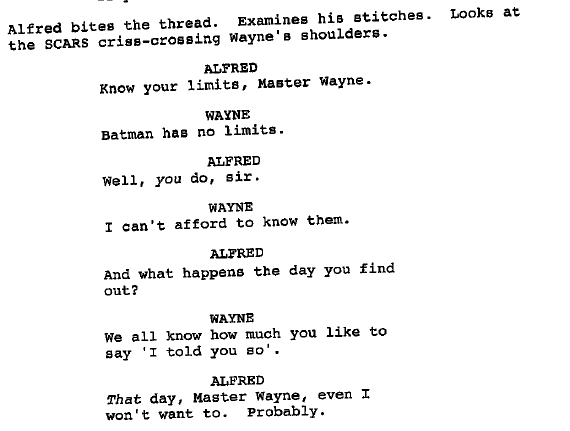

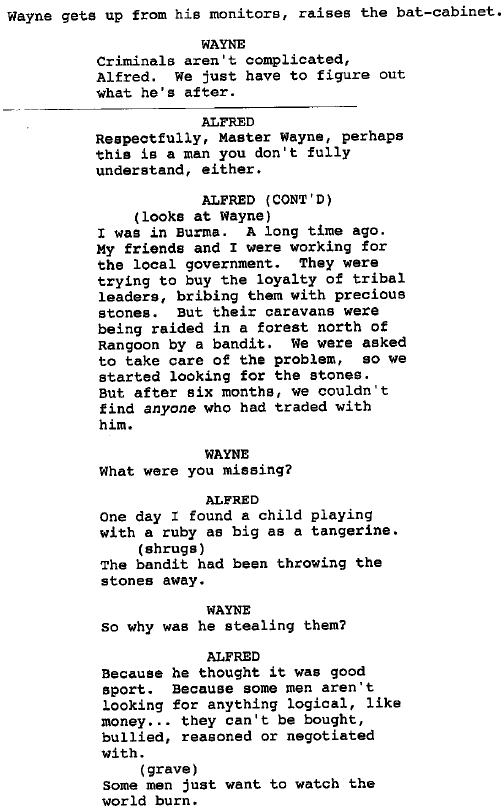

The opening of the film finds Bruce Wayne testing the limits of Batman’s longevity in this world, but he is in denial that Batman can’t withstand everything. His butler, Alfred, frequently tries to show him the truth:

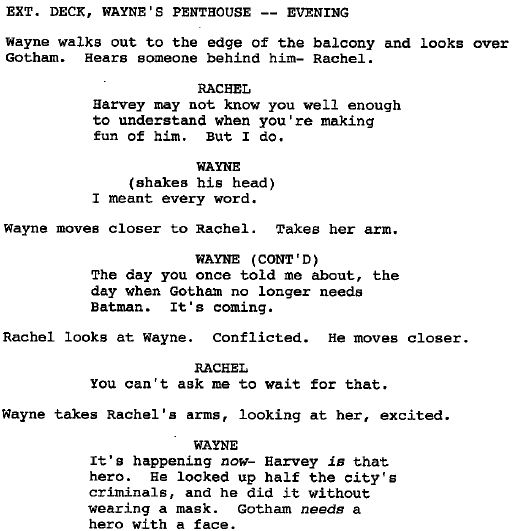

Luckily, Wayne has a glimmer of hope that he can step away from his crime-fighting days in the form of Gotham’s intrepid new District Attorney, Harvey Dent. He believes the virtuous and unblemished Dent is the future savior of the city, not Batman:

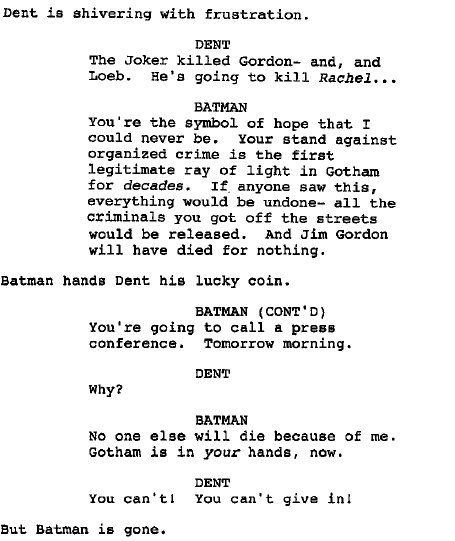

But Batman soon learns that Dent is not a perfect man. Dent proves to be just as crooked as the criminals when he wants to be, and in his desperation to save Gotham, he shows willingness to take extreme actions to bring about justice. Batman recognizes that in order for Dent to be the hero Gotham needs, he can’t have these faults, and he can’t stoop to the morally-ambiguous level that Batman does in order to fight crime.

Batman’s goal and motivation is for Harvey Dent to take up the mantle as Gotham’s protector, but in order to do so, Dent’s reputation must survive unscathed. And as Batman comes to understand that even Dent is corruptible under the right circumstances, he realizes that his previous conviction about the incorrigibility of man (and Batman’s immortality) is false.

This question of inherent good and evil sets up the central conflict of the second half of the story and brings us to the best part of the film: our antagonist.

A Scalpel, Not a Hammer

By far the most memorable aspect of this movie is Heath Ledger’s stunning performance as the Joker. He elevates an already-good movie to new heights with his unhinged take on the villain, challenging Batman at every step with carefully-controlled chaos. Ledger’s acting is unforgettable of course, but the Joker is well-conceived in the screenplay as well, a strong and necessary counterpart to Batman that drives the narrative forward organically.

A primary reason the Joker is so effective at fighting Batman is that Batman doesn’t fully understand his motivation at first as a result of his own shortcomings:

The Joker shares a lot in common with the antagonist of another film that came out less than a year before this one, No Country for Old Men‘s Anton Chigurh. Both men embody the spirit of chaos, of causing trouble for its own sake…the other characters of their respective films have such trouble dealing with them because they fail to grasp this. Because Batman has a pre-established worldview that criminals do what they do out of circumstance rather than nature, he is unprepared for the threat posed by a criminal so unabashedly and irrefutably evil at his core.

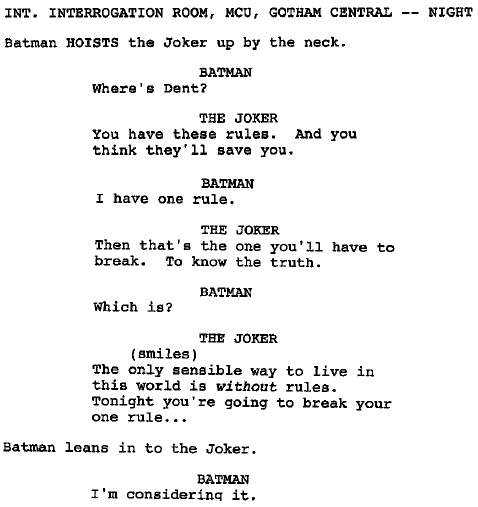

Meanwhile, the Joker understands Batman perfectly well. He knows that Batman has flaws as a hero and attacks them specifically, like Batman’s refusal to kill:

It would be pretty easy to throw a character like the Joker into any old film and pit him against the hero to solid effect. He seeks to upend the established order and spread fear for its own sake, so regardless of his plan or who his opponent is, he becomes a force needing to be stopped, leading to a fun story. But what makes him so special for The Dark Knight is that he has a specific motivation and goal: he wants to subvert Batman’s moral code and prove that even the best of men can be corrupted. He attacks a specific weakness of Batman perfectly: namely, that Batman has rested his future on Dent’s shoulders, or more broadly, on the inherent goodness of mankind.

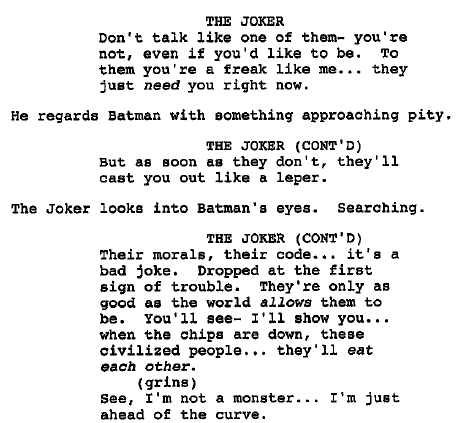

The Joker believes that Batman’s convictions are wrong, and he sets out to prove why he is wasting his time trying to help the “good guys”:

A good villain in a superhero film is one that has a specific message, one that makes us think “hmm, maybe he has a point,” even if we disagree with his methods. All good supervillains have this trait. Killmonger disagrees with Wakanda’s stinginess of resources and neglect of worldwide black oppression in Black Panther. Magneto believes mutants should shed the notion of peaceful co-existence with the humans who reject and belittle them in X-Men. Syndrome of Pixar’s The Incredibles has a bone to pick with superheroes selfishly hoarding their powers and lording over regular people like gods. And in The Dark Knight, the Joker believes the facade of morality is a farce, and he sets out to expose the hypocrisy of men (and the Batman) by bringing out the worst in them.

Caught in the Crosshairs

Harvey Dent therefore becomes the focal point of Batman and the Joker’s war for the battle of Gotham’s soul. Batman sees Harvey as the hero Gotham needs, the indomitable force of good willing to tackle crime head-on and bring about legitimate change from within. The Joker knows this and seeks to prove to Batman that even a boy scout like Dent has a tipping point.

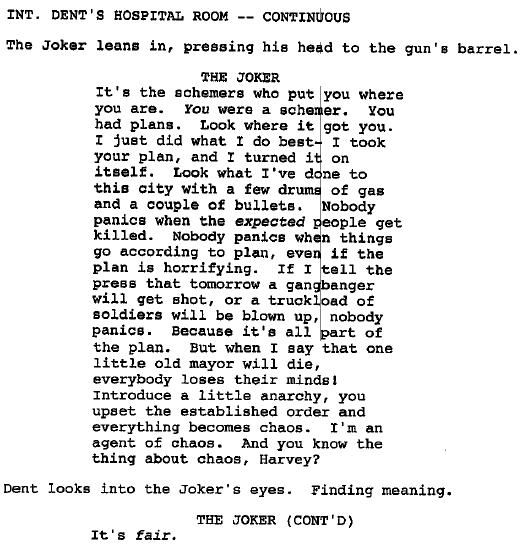

In order to accomplish this, the Joker first demonstrates to Dent how unfair the world actually is. Dent has a moral code of his own, as exemplified by his lucky coin with two heads: he makes his own luck and believes he is control of his own destiny. After Rachel is taken away from him due to essentially a coin flip (Batman could only reach one of them in time), the Joker arrives to upend his worldview and push him over the edge into madness:

As the Joker’s master plan starts to fall into place, he sets up a demonstration to show Batman first-hand what the true nature of humanity is. He rigs two ferries to explode – one filled with innocent citizens, the other violent criminals – and gives both sets of passengers the detonator for the other ship, daring them to press it and prevent the other from killing them first. But when this fails to produce the results he expected and neither ferry kills the other to save themselves, the Joker is forced to revert back to his original scheme.

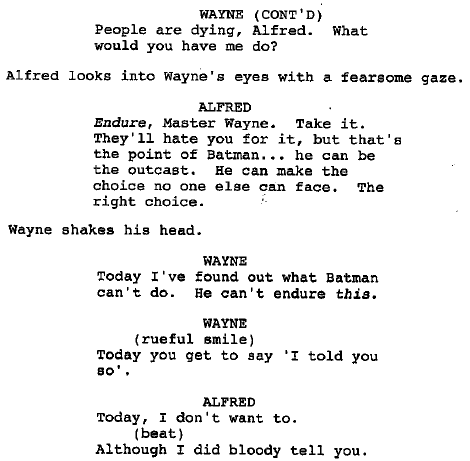

And sure enough, Harvey Dent soon rampages through the city as Two-Face, an extension of the Joker’s nihilistic and chaotic viewpoint of the world, reducing people’s fates to the mere flip of a coin. Batman knows that defeating the Joker isn’t as simple as overpowering him and getting him arrested. If the public learns how easily Dent was corrupted, the city could fall into chaos and the Joker will have beaten him. So after saving Gordon’s family and causing Dent’s death, Batman makes his final choice: he takes on Dent’s burden and allow Gotham’s “white knight” to live on in death.

Batman’s character arc comes to a close in The Dark Knight as he embraces his role of Gotham’s silent protector. He had hoped at the beginning of the film that a day would come where the city no longer needs him, but the Joker has proven that such a day is not close at hand. Batman has lost: he was wrong about the inherent goodness of mankind, and he is forced into hiding as a direct result of the Joker’s scheming. This sets up the events of the sequel, The Dark Knight Rises, in which the Joker’s plan finally comes to fruition and the city’s lowlifes rise up against the establishment in protest of Harvey Dent’s crimes and the police cover-up. It makes Heath Ledger’s death all the more sad when you think about how much better the final film in Nolan’s trilogy could’ve been if we got to see the Joker continuing to pull the strings behind bars, or whatever else Nolan had in store for us with the character.

Conclusion

What does The Dark Knight teach us about how superhero movies ought to function? First of all, that they begin with strong characters. And strong doesn’t just mean powerful…every great hero has a weakness, and an equally-strong force of antagonism seeking to exploit that weakness. Furthermore, the hero’s conflict should come from within, and in order to overcome the villain, he/she must challenge the beliefs they held dear at the start. If that doesn’t happen, we end up with emotionally-bankrupt fare more interested in flashy set pieces and doomsday scenarios than legitimate character conflict.

So as we all file into the theater this weekend to watch dozens of CGI-generated freaks of athleticism wage war against an intergalactic supermonster to save the universe, let’s try to remember the simple formula that drives great cinema: a motivated protagonist with clear goals and desires, and an equally-motivated antagonist seeking to disrupt them. Only once we have that key ingredient can we dress it up with as much ridiculous action as we want.

VERDICT: A+

-AD

All images courtesy of Warner Bros. Studios.

Other Five Faves entries:

- Pulp Fiction (1994)

- In Bruges (2008)

- The Social Network (2010)

- Whiplash (2014)

6 thoughts on “Five Faves #3: “The Dark Knight” (2008)”