Welcome to the second installment in my Five Faves series, in which I discuss the five movies that I consider my all-time favorites. Last time we dove deep into the screenplay of Pulp Fiction to determine what makes it so special. Today we explore the cinematic debut of former playwright Martin McDonagh, 2008’s In Bruges. While McDonagh later found mainstream success with awards darling Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri, it was his first creation that resonates the strongest with me.

The film tells the story of two hitmen (Ray and Ken) hiding out in the titular Belgian town after a job goes bad. While waiting for further instructions from their boss (Harry), they take in the local culture, get into various misadventures, and reflect on their past lives. The film takes on a darkly comedic tone with outlandish scenarios and boorish behavior, but underpinning everything is a serious examination of guilt and redemption.

Detectives on the Case

I’ll be the first to admit that the flow of the film will be too slow for many viewers unfamiliar with McDonagh’s work. It’s a film that barely transcends the boundaries of a play after all, with most scenes involving just two characters sitting in a room talking. Furthermore, the premise is rather dry…the film begins with Ray and Ken arriving in the sleepy town of Bruges to hide out after a hit gone wrong. We don’t even get to see the hit take place, only the aftermath! So how does McDonagh establish pace early on when we aren’t really sure what kind of film we’re in for yet?

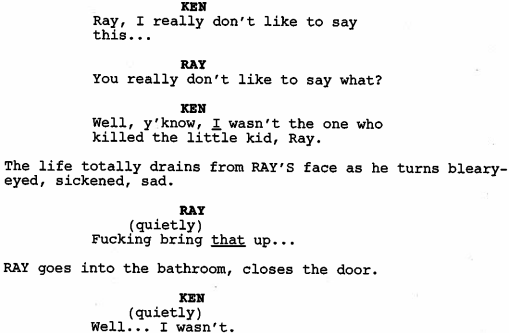

From the first few scenes, McDonagh establishes a sense of mystery and intrigue to the plot. We get glimpses of something bad happening that forced them to flee Britain, but we only hear about it in snippets. The film starts not with said thing happening, but as two strange men are sightseeing in Bruges, with us wondering what the hell is going on. Soon into the action we learn that something truly terrible has happened:

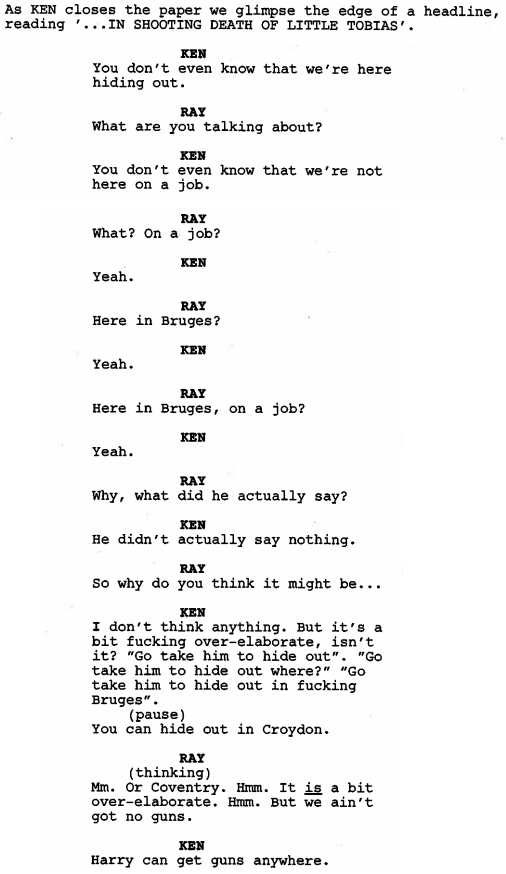

This is the only exposition we get amidst the whimsical sightseeing that opens the film. Already our minds are racing: did Ray really kill a kid? Why? Was he supposed to? Who gave the orders to kill? Was it the same person who gave orders to flee? Soon after, we get a conversation between Ray and Ken discussing the nature of their visit:

We have three questions rattling around in our heads at this point in the film: 1) What exactly did Ray do to this little kid, and why? 2) Why are they in Bruges of all places? and 3) Who is this mysterious Harry fellow that they seem to revere and/or fear so much? Nothing has actually happened yet, nor has anything been revealed to us, but McDonagh manages to plant these seeds early to make us seek the answers. So despite not much engaging us visually or conceptually, we become an active audience, recognizing that our lack of information is intentional as we move forward with a detective-like approach to the plot.

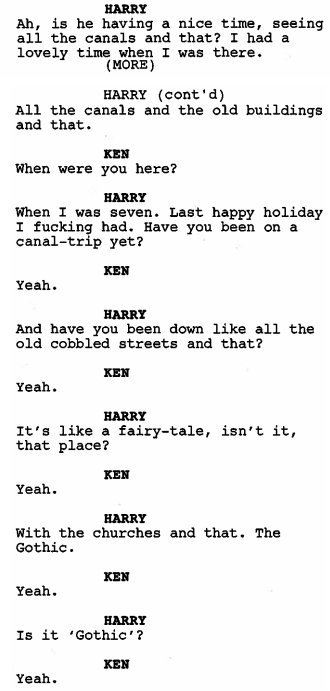

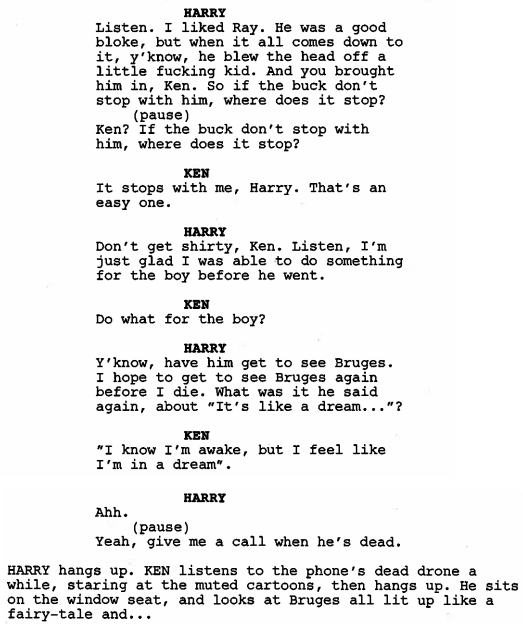

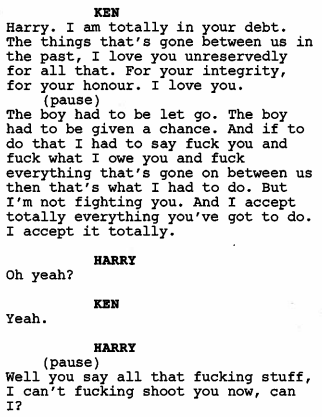

My favorite scene in the entire movie (and one of my favorite scenes ever) is when Harry finally calls and he and Ken talk in private about Ray. The scene meanders for pages and pages, with some physical comedy mixed in with seemingly-pointless small talk, and again we wonder what is going on, searching for clues:

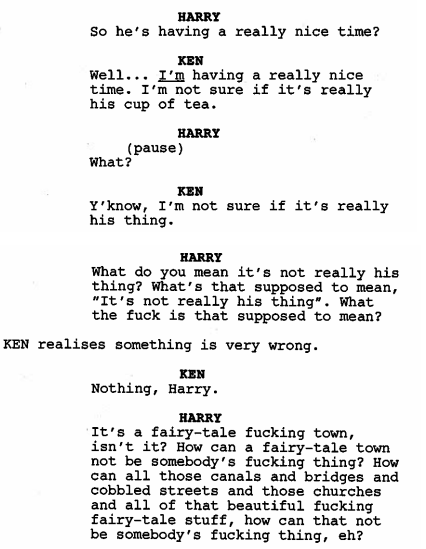

This phone call has been built up as this big, significant, important event for the entire first act, and here’s Harry making trite small talk. Even Ken is confused, mirroring the audience: when is he gonna get to the damn point? But it doesn’t take long before the conversation takes a sharp turn:

Ken spirals into damage-control mode, realizing that he needs to appease his boss by playing along with this charade even though he still doesn’t know why it’s so important to Harry. It adds urgency to the scene, informs Harry’s character even further by portraying his short temper, drives a wedge between Ray and the mercurial Harry with Ken playing mediator, and most importantly, it establishes history between Harry and Ken, something that very few screenwriters pull off well. Even though this is the first on-screen exchange between the two, we get the sense that they’ve known each other long enough to really know each other, as Ken is quick to realize when he’s set the guy off.

And finally, Harry’s true purpose for the call and all the small talk becomes clear:

The true purpose of the trip is finally revealed nearly halfway through the film: Ken is there to kill Ray, and Ray is there to enjoy his last days before meeting his judgment. Harry takes on an almost God-like persona at this point, speaking from afar and passing on messages and orders to his followers. He passes final judgment on Ray and it’s implied that his word is final. This sets up the central conflict of the film: does Ken obey Harry’s orders or make up his own mind about Ray’s life?

Ideologies Manifest

We’re knee-deep in analysis already and I haven’t even touched on the characters yet…usually the very first thing I talk about in a screenplay. What makes this film so unique is that McDonagh takes the hidden-information technique and applies it to everything, including the characters themselves. We don’t fully understand what everyone wants and how we are supposed to feel about them for quite some time, and while usually that’s a negative, here it’s very much by design. And because the characters are so ingrained in the metaphor underpinning the plot, only once we understand the macro-stakes involved can we start to unpack and understand the characters fully. In addition to the usual techniques of differentiating their dialogue through dialect, vocabulary, and general attitude, each character represents a specific force in the cosmic battle being waged between moral relativism and moral absolutism.

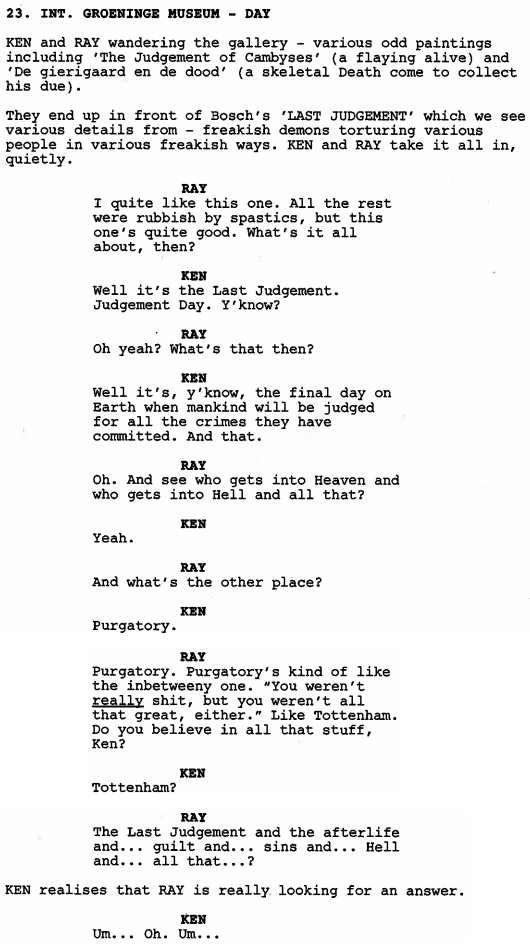

At its core, In Bruges is a film about redemption versus revenge. Ray, our protagonist, is wracked with guilt for accidentally killing a little boy. Bruges is his purgatory, where Ray is left to his own devices to contemplate his actions and reckon with the crimes in his past life. The central question at stake is: can people atone for their sins, or are they doomed to condemnation for them? This theme is even presented to us very early in the film, as Ray and Ken sight-see in a museum, before we understand its significance:

McDonagh is able to mask the significance of this scene in a few ways. The motif of these two characters sightseeing, and placing this scene between various shots of the two observing other ancient historical sites, helps soften the hard-hitting questions. The deliberately-slow pace of the first act seeks to put us in the same “bored” mindspace as Ray, following along as Ken drags us around museums and churches, and we might miss these small moments while waiting for the action to pick up. The comedic deflections keep us engaged in other ways, highlighting Ray’s endearingly-childish sensibilities and keeping the tone light.

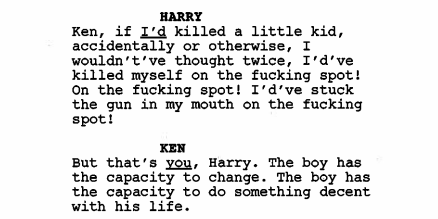

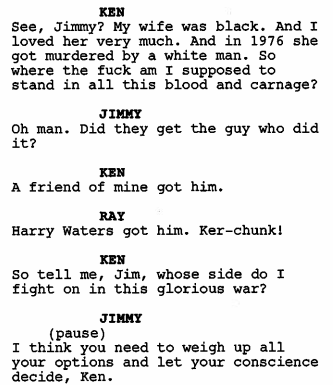

What’s fascinating to me about the character construction here is that, although Ray is clearly the central focus of the film, he’s not necessarily a protagonist. He’s treated more like a specimen in a test tube, while the true protagonist (Ken) engages the antagonist (Harry) in a war for Ray’s soul. They represent the opposing viewpoints regarding moral relativity while Ray is the subject of their debate. The main conflict of the film begins when Ken refuses Harry’s request to kill Ray for his crime. Their disparate mindsets on the incident reflect on what ideology they represent:

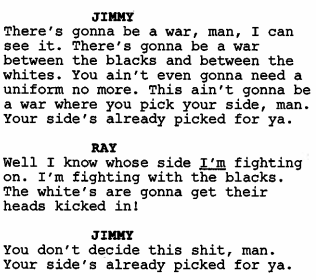

We get little hints about Harry and Ken’s own backstories and experiences that led them to their differing beliefs. In a notably absurdist humor scene, Ken and Ray do cocaine and listen to Jimmy the dwarf rant about an impending race war.

After a prolonged back-and-forth between Ray and Jimmy, Ken jumps in to challenge Jimmy’s simplistic and partisan view on the world:

In defense of McDonagh’s controversial fixation on offensive humor, it serves an important purpose in In Bruges. The patent absurdity of the situation is intentional: by crafting the most black-and-white scenario possible (a literal blacks vs. whites war), McDonagh is then able to cast doubt on the whole notion of rigid morality. First Ray, with his simplistic and childlike curiosity, pokes holes in his logic by asking where the mixed-races, Pakistanis, and Vietnamese would stand in the war, then Ken completely undermines the concept with his half-sarcastic moral conundrum.

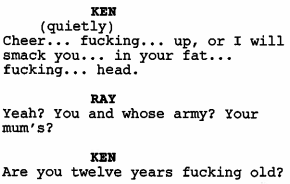

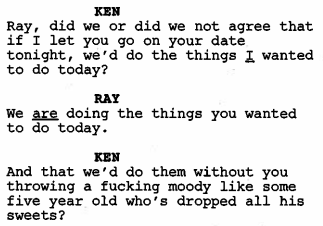

Ray frequently finds himself in scenarios where he makes inappropriate jokes and remarks about controversial topics. He commits a faux pas by calling dwarfs “midgets,” he attacks Canadian tourists after mistaking them for Americans, and he insults an overweight family by calling them elephants. By comparison to the “adults” Ken and Harry, Ray is extremely childish and immature. He’s commonly referred to as “the boy” by both Harry and Ken, and he is reprimanded for his boorish behavior quite often. Ken and Ray’s dynamic is that of a parent trying to wrangle their young child in public and make them behave. Ken even calls Ray’s age into question multiple times:

There’s a deliberate parallel between Ray and the boy he kills. Ray sees himself in the boy because he, too, is relatively young and has/had so much of his life ahead of him. The frequent allusions to his youth accentuates the fact that he is reckoning with the long life of guilt ahead of him, and whether he thinks he deserves it:

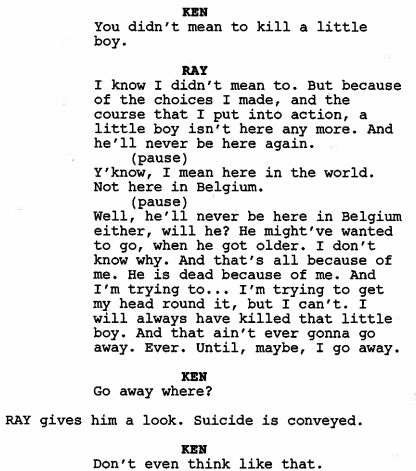

Although Ray isn’t necessarily the protagonist, he has a choice of his own to make: does he live on and attempt to atone for his mistakes, or end it now and bring justice to the boy? There is a scene in which Ken arrives to carry out Harry’s orders, only to discover Ray about to commit suicide and stops him, another case of absurd irony. It draws a clear distinction between condemnation preordained and self-inflicted, in which there is tension between Ray making the choice for himself or someone else making it for him.

Circular Logic

Now I don’t like to go around throwing out words like “perfect” to describe things very often, but this screenplay damn near approaches it. When a writer is able to engage the reader early with intrigue, entertain them with action and humor, AND tie it all together neatly at the end, it’s a beautiful sight to behold. It’s reminiscent of Pulp Fiction, despite not having a nonlinear narrative, in that the film throws out random non-sequiturs for our entertainment but still manages to bring them back into the fold by the end, proving that the twists and turns were not arbitrary. Every single scene in this film has a specific purpose for existing, often accomplishing multiple things at once without us even realizing it.

Lots of little interactions that are seemingly just for comedic effect end up coming back to relevance later. Ken tries to get rid of his coins at the bell tower, but the cashier won’t accept them; this allows him to later drop them off the tower to warn Ray. Ken pretends to shoot Ray with a finger gun from the top of the tower, foreshadowing the fact that he’ll be tasked by Harry with actually killing Ray. The fat American tourists rebuke Ray and Ken’s insistence that they don’t try to climb the tower; one of them later has a heart attack climbing it, causing it to be closed for the final act. Ray beats up the Canadian tourists during his date with Chloe, which sets up his arrest and return to Bruges when he attempts to flee by train. Ray’s violent confrontation with Eirik leads to the young man ratting him out as Harry searches for him. Harry purchases hollow-point bullets on a whim out of vanity, which becomes relevant at the very end after shooting Jimmy (which we’ll discuss in a bit). It’s moments of foreshadowing like these that are only best appreciated upon repeat viewings.

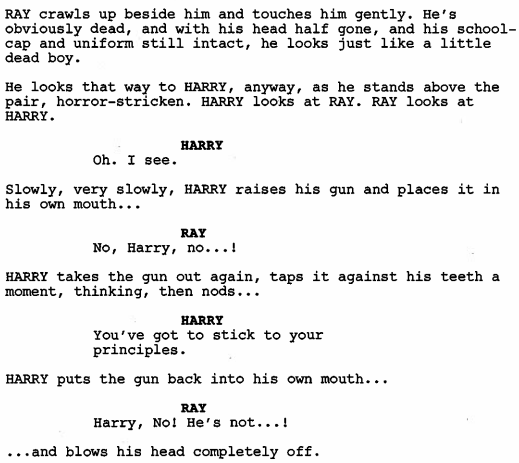

The character of Harry, who only appears in the second half of the film, has an interesting circular arc as well. While he initially appears brutal and violent by nature, it later becomes apparent that he is only so out of a strong moral conviction and code of honor. We first see this when he confronts Ken, intending to duel him to the death, but Ken refuses to fight back:

Harry is not indiscriminate in his violence; he only uses force when he deems it proper justice. And furthermore, he is willing to follow through with his beliefs when he is the one breaking his own rules. After he shoots Jimmy the dwarf accidentally and mistakes him for a child, he does not waver in his resolve for even a moment:

The payoff of this moment has been set up by an entire film’s worth of dissecting Harry’s character. By subverting our expecatations of this man at every turn, and establishing how he chooses to interact with the world, McDonagh manages to both shock us with Harry’s decision and help us make sense of it at the same time, a phenomenal feat. What before seemed like exaggeration for effect (“I’d’ve killed myself on the fucking spot!“) is now revealed as unambiguous dedication to an ideal.

At the end of the film, Ray is near death from Harry’s killing blow, and he suddenly decides that he wants to live. He decides to take his fate out of his own hands, and even out of Harry’s, and put it in the hands of the mother of the slain boy for the fairest possible punishment. Ray’s experiences in Bruges have led him to believe that life is worth living, even with the guilt weighing on him. All the events of the film – the meaningless in-between moments, the misadventures and romance and fun – add up to an experience that Ray wants to continue, even though the little boy never got the chance.

Conclusion

In Bruges is a film that grows on me every time I re-watch it. What appears at face value to be some mindless-fun dark comedy is indeed a much deeper examination of the human condition and a near-flawless screenplay that establishes Martin McDonagh as a cinematic force to be reckoned with. The twists and turns are all well-earned and carefully planned for maximum effect, the dialogue is smart and endlessly quotable, and the characters are charismatic, consistent, and memorable. It remains one of the most clever and “complete” screenplays I’ve ever read.

VERDICT: A+

Thanks for checking out the second installment of my Five Faves series. Quick update: I have decided to indeed make my analysis of The Dark Knight a retroactive member of the Five Faves series, so we’ll consider that one the third entry. As such, look forward to entry #4 in the coming weeks as I discuss the penultimate film in my pantheon!

-AD

All image rights belong to Universal Studios and Focus Features.

Other Five Faves entries:

- Pulp Fiction (1994)

- The Dark Knight (2008)

- The Social Network (2010)

- Whiplash (2014)

6 thoughts on “Five Faves #2: “In Bruges” (2008)”