It’s a shame to me that 2016’s Moonlight will always be remembered as the film that “stole” Best Picture from La La Land, because it truly was the best film of that year (and one of the best films of the decade). Barry Jenkins’s direction, the gorgeous cinematography, and flawless acting add up to a stunning piece of art. But today we’re looking at the screenplay alone for its own merits and determining what makes it such a compelling work before any visual flair is added. Did social politics play a role in its big Oscar win? Maybe, maybe not. That doesn’t mean that it wasn’t a deserved win, because Barry Jenkins’ film is a masterpiece.

Unspoken Truths

I’ve talked in the past about the merits of descriptors. Often when you think of a screenplay, you think dialogue, because that’s the most obvious thing that translates directly from page to screen. But a good writer knows when to expand on the in-between moments, in the margins that the audience doesn’t see. Barry Jenkins could have easily cut corners because he knew he would be directing the film himself and could add in all the emotion during production, but he takes care to flesh out every aspect of the story, from intent to emotion to mood. Because of this, Moonlight‘s screenplay at times reads like poetry.

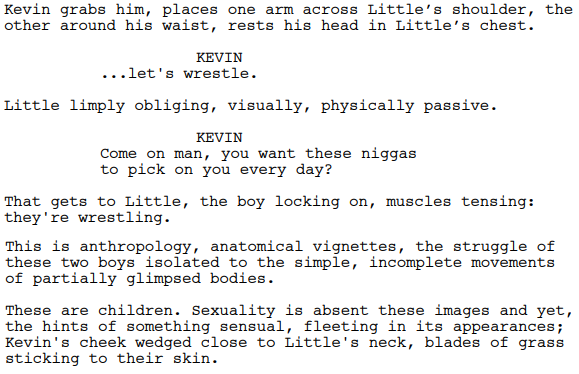

One common thing Jenkins does is use his descriptors to convey tone. Consider an early scene in which Little and Kevin wrestle:

Sensual but not quite sexual. Physical but not quite intimate. Jenkins is making it clear what the purpose of the scene is so that it can’t possibly be misconstrued. We understand just from the page what Little’s struggles and emotions are thanks to the subtle nuances of the script like this. His desire to be “tough.” His physical sensuality. The pressures on young black boys in the projects to act a certain way. All of this is conveyed without words, with simple images and descriptions of two boys wrestling in a field.

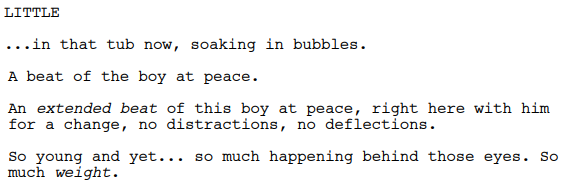

There is a saying among filmmakers that “the eyes are the windows to the soul,” and Jenkins really takes that to heart. He focuses on Little’s eyes often, using them to signify deeper pain or sorrow than what’s spoken aloud:

We understand the pain of growing up poor, of not knowing exactly what you’re feeling, just from his expressions…not an easy thing to direct an actor to do, and certainly not an easy thing to convey on the page. But Jenkins makes efforts to do so anyway, knowing that this is the key to the story: translating inner turmoil into external conflict.

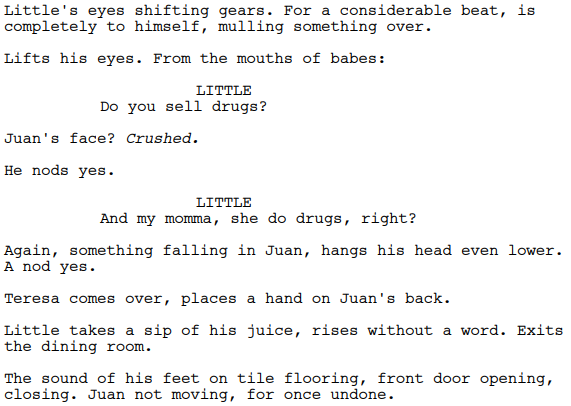

Starting Little’s story from young childhood fits this theme perfectly because children are often the most likely not to understand their own thoughts and feelings. Jenkins invites us to learn things along with Little, to watch him process new information in real time, seeing the gears turn in his head. We catch every little movement or reaction that Chiron does, which shapes his understanding of the world:

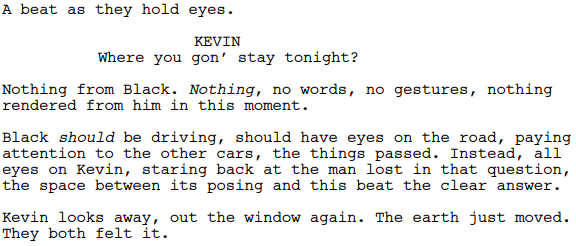

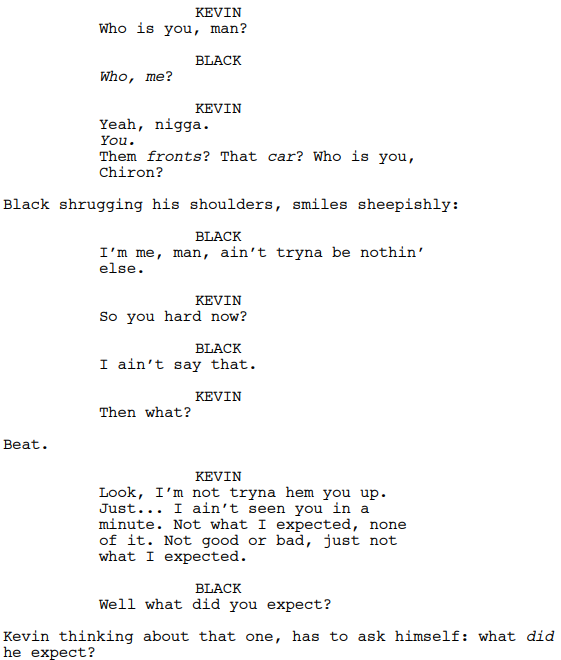

Even when Chiron grows up, he continues to struggle with this self-expression. His repression of identity causes further strain on his relationships with others and continues the need for the audience to read the subtext of what he’s thinking. When Chiron (now “Black”) visits Kevin as an adult and is still unable to say what he’s feeling, the implication is everything:

Watching the film, I was struck by just how much was left unspoken between characters, and how often the dialogue on-screen didn’t seem to match up to what we know the characters to be thinking. And that’s very much by design, baked into the very fibers of the screenplay. Jenkins is way more interested in the subtext than the text, trying to make us understand what characters mean just as much as what they say.

Defense Mechanisms and Toxic Masculinity

As we now know, Moonlight is a story about a gay black man discovering his identity and embracing it. But it’s so much more than a “gay film” in that Jenkins explores other aspects of homosexuality, including its effects on masculinity and putting up fronts for other people. Chiron’s journey isn’t just one of coming out of the closet, but breaking down the walls he’s erected around himself as a defense mechanism, not allowing anyone else in.

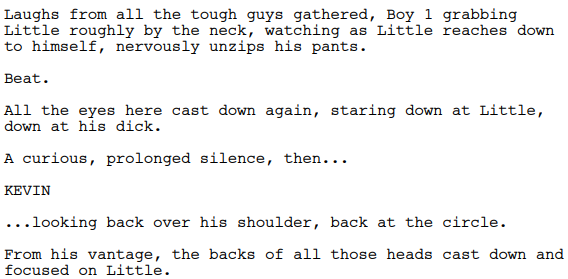

Even as a young child, Chiron is concerned with fitting in, and he believes that the way to do this is to act tough. In his world, manliness is everything, even before the children really understand what that means. An early scene features a group of boys literally comparing dick sizes, knowing already what society expects their most important asset to be:

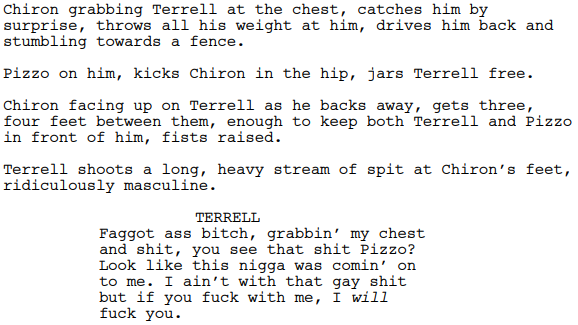

As Chiron grows older into a teenager, and he (and everyone around him) has a better understanding of what makes him different, it’s the thing that other kids use to set him apart. He has been called a “faggot” since childhood, and now that he starts to realize why, it cuts even deeper. Even in non-sexual context, his tormentors take every opportunity to point out his supposed differences:

Moments like these speak to the default mindset of the black youth around Chiron, who see sexuality, masculinity, and power as intrinsically-linked. They take pride in making sexual references to Chiron’s mother, and attack any perceived weakness as gay. It helps us understand the person Chiron becomes (the hardened Black) when projecting manliness is a defense mechanism against bullies (and society as a whole).

Kevin is one of the few people who knew Chiron from childhood all the way through to adulthood, so he is the most surprised by his transformation.

Because we’ve been following Chiron’s journey so closely, we know what factors led to his metamorphosis into macho-man. But for Kevin, the boy he grew up knowing just disappeared and became the opposite of what he expected. Kevin knows Chiron’s true self, revealed to him during their intimate moment on the beach, and didn’t expect Chiron to become his bullies. He’s the first to key in on Chiron putting up fronts, knowing that what he projects to the world isn’t who he really is. Chiron’s journey comes in accepting Kevin’s insistence that he put down the walls and let his true self breathe.

Time and Identity

There is an interesting dichotomy at play underpinning the script. Jenkins frames the story in three parts, one act each depicting a different time in Chiron’s life, giving him different names and portraying him with three different actors as though he is literally a different person in each stage. Yet at the same time, Chiron’s arc is consistent throughout the film, as though he is still the same person but dealing with his problems in different ways. That juxtaposition makes for an interesting commentary on how people’s identities are a constant over time, but they change how they react to the world.

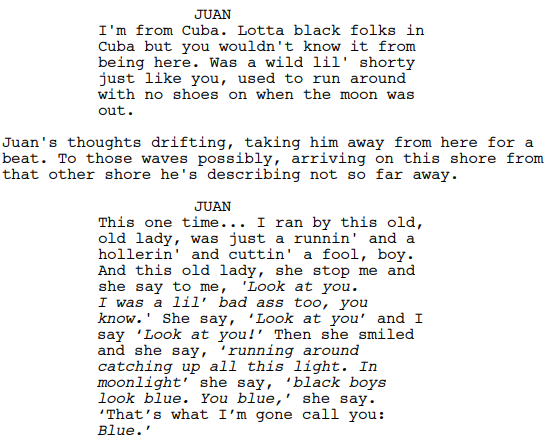

The title of the film, Moonlight, is the ultimate evidence of this. In a tender moment at the beach, Little’s protector Juan tells the story of how he earned the nickname “Blue”:

There are two alternate interpretations of the significance of moonlight in the film. One is that, under moonlight, black boys can be self-expressive and don’t have to put up fronts. The other is that, to Juan, it’s an example of society imposing its own expectations on him without his say. He didn’t ask for the nickname Blue, and doesn’t want to let other people’s opinions shape his identity. Juan’s message for Chiron is to define his own identity, not succumb to the pressures of other people. This is the lesson Chiron must learn throughout his journey: that while his peers expect him to be a hardened thug, he has the power to define his own life.

At each stage of Chiron’s journey, his name indicates the specific pressures beset on him. He is “Little” at the film’s start because he defines himself by his tormentors. He learns from Juan not to allow that to dictate his persona, so by Act II, he is “Chiron,” his given name. This reflects the pressures at home from his mother, and his insecurity about his future. Chiron is able to overcome his school bullies one way or another, but he still has unresolved tension at home and lacks the supportive upbringing he desires. In Act III he adopts the moniker “Black,” a nickname given to him by Kevin, implying that his final hurdle is in shedding the hard persona he’s built for himself. Kevin is the one person who understands Chiron’s struggle, and the fact that Chiron clings to the nickname Kev gave him suggests that he longs to return to that stage of his life, that moment on the beach where he could be himself.

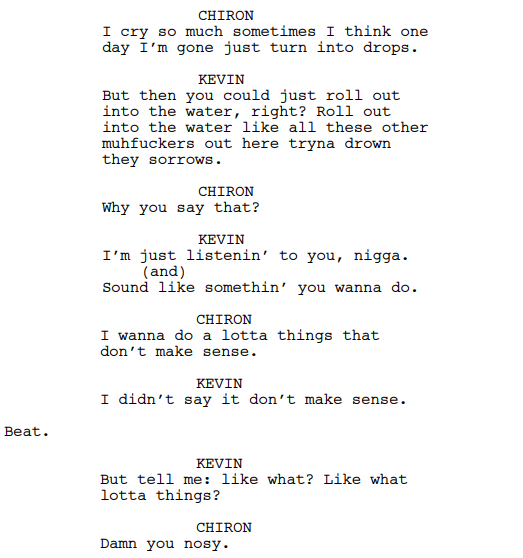

It’s also fitting that in Act II, when he goes by his real name, he reveals the most about his true self. Previously he was too naive to understand it, and later he is too repressed to express it, but in his teenage years, Chiron is the most open and aware of his true identity. The closest he comes to divulging his true thoughts is on the beach with Kevin:

It’s almost as though Chiron feels he slipped up and gave away too much, and as soon as Kevin tries to dig deeper he recedes back into his shell, back into the protective barrier he’s built to save him from harm. With Kevin and Kevin alone, he feels safe enough to be himself, so his arc ultimately comes full-circle back to him as he attempts to break free of the cycle of repression. The three-act structure reflects Chiron’s journey: 1) His discovery of the world and who he thinks he is, 2) His crucial turning-point in which he decides which path he wants to go down, and 3) His transformation into something he’s not and his realization that he needs to change.

The decision to cast three different actors for the same role symbolizes this beautifully. Chiron may feel like three different people, shaping himself according to what society wants each time, but ultimately he decides what he wants for himself, fulfilling his desire for Kevin (and by extension, for openness and freedom from judgment). He makes peace with his past by forgiving his mother for her sins, and moves forward with the mindset that Juan impressed upon him in his youth: that only he can dictate his future. The film ends with a shot of Little on the beach in the moonlight, turning back to us…Black has confronted his demons and shed all his personas, allowing his true self to shine through.

Conclusion

We can point to a lot of things about Moonlight that make it special, from its gorgeous shot selection, the score, the acting, the editing, the symbolism, and more technical brilliance. But its screenplay is the foundation, guiding the production forward with strong characters and thematic ties, telling a unique story in a unique way. It not only tells us about a repressed young man learning to free himself…the film mimics Chiron’s inabilities to express himself and forces us to read between the lines to figure out who he really is. Again, I must express my frustration with the narrative surrounding this film, that people are derided for claiming to like this film just because of its social importance, because it is far from the case. This is a beautiful work in its own right, regardless of subject matter and race and sex and all that jazz: cinema at its purest, telling a compelling human tale in the most immersive way possible.

Did Moonlight deserve Best Picture? Is it a masterpiece? Is the conversation surrounding the film fair? Will it stand the test of time, or be forgotten years from now?

-Austin Daniel

All image rights belong to A24. Script excerpts courtesy of DailyScript.

11 thoughts on ““Moonlight” Script Analysis: Conveying the Unseen”