We’ve reached the end of my Five Faves series, chronicling my five favorite films of all time! We’re ending the series with a bang today…pun intended, because we’re talking about Damien Chazelle’s Whiplash, following an ambitious jazz drumming student (Miles Teller) who is taken under the wing of abusive instructor Terrence Fletcher (J.K. Simmons). The film earned significant accolades during its theatrical run, nabbing three surprise Oscars, but I feel it deserves even more credit than it’s gotten. This is a modern masterpiece.

Rise and Fall

Whiplash is not your typical musical film. It’s closer to a sports action or war drama film, and you could even call it psychological horror in a sense. It’s perhaps the most cerebral film of the past decade, aiming to put you in the protagonist’s shoes and feel every sensation, every thrill, every high and low of the plot. Young Andrew’s quest to reach the pinnacle of musical achievement takes us to some extremes, as the tyrannical Fletcher attempts to stamp out any remnants of hesitation or weakness from Andrew (and us in the process). But the film is structured such that we get moments to breathe in between these intense sequences of conflict, which both heightens the moments of terror when they do come and allows a release valve for the built-up tension in the audience. If the film was just an hour and a half of JK Simmons screaming at people, we would become desensitized to it and moments of terror would lose some of their impact.

Chazelle plays to the theme of drumming well, as rhythm/tempo is a recurring theme in both the plot and tone. Like a conductor, he knows when to bring these to a noisy crescendo and when to let tension dissipate into momentary silence. His ability to vacillate between the two with ease is nothing short of impressive. The film begins and ends with an ever-rising pattern of drum hits, hinting strongly that this is more than just a recurring theme, but a salvo for the entire film:

The allusion to gunfire is meant to make us uncomfortable, like we ourselves are under assault, and as the drum beats increase in tempo, so too does our blood pressure. We know before we even see the first image that we’re in for many ups and downs, and as music ebbs and flows, so too does the tension.

Nowhere is this more apparent than with the sideplot of Andrew’s girlfriend, Nicole. Three are three major sequences involving her, interspersed throughout the film to give us less demanding fare that is easier to parse and swallow in the moment. These scenes are calmer and show Andrew when he’s not on-edge, allowing us better insight into his character in its natural state. And because of this, the three sequences each offers a glimpse into the broader changes happening in his life: when he asks Nicole out, he’s a wide-eyed innocent, still open to the possibility of love. When they go on their first date, he’s beginning to fall into Fletcher’s clutches, and he calls her career uncertainty into question, indicating that he values success above all else. And finally he breaks up with her, completing his descent, unable to see a future in which he can have happiness and success at the same time.

All of this happens in the “valleys” of the film, so we simultaneously get to take a break from the relentless pace and still progress through Andrew’s arc. In the high moments we see Andrew pushed to the brink, Fletcher’s torment eating away at his resolve, while in the low moments in between we see the little ways that he’s changed as a person. Then when the next high comes, the stakes have been raised even further, and we get to take what new information we’ve learned about Andrew (and Fletcher) to increase our enjoyment of the battle.

Although this pattern of ups and downs is clearly established early on, Chazelle knows when to break from the norm in order to highlight a crucial moment or two. Just as we begin to settle into this repetition of rise and fall, Chazelle finds ways to subvert expectation and ratchet things up even more. One of the most jarring sequences involves Andrew getting into a car crash on the way to a crucial performance:

In any reasonable scenario, the car crash would have ended the sequence. Cut to black, wake up in the hospital, begin Act III. But we’re not even close to done. The scene draws out: first Andrew goes back for his sticks, then he runs away from the crash site, then he makes it to the performance, then he gets on stage, then he plays with the band (poorly), then he attacks Fletcher, THEN we’re on to Act III. By constantly building on top of an already-tense situation, Chazelle manages to elevate a cliched moment we’ve seen a million times to a nail-biting sequence that plays against the audience’s desire to slow down. And that’s a credit to Chazelle’s dedication to fostering this expectation throughout the first two-thirds of the film.

Ultimately the musical motif comes back into play during Andrew’s final performance. The sequence begins as we might expect: Andrew fails when he is given the wrong sheet music by Fletcher, rushes offstage to the comforting arms of his father, returns to lead the band in a triumphant song, and Fletcher cues the outro. Happy sports ending, right? One that we’ve seen a million times. But again, Chazelle keeps the ball rolling:

Not only has Chazelle worked the audience’s expectation of the plot’s rhythm against us, he has played against our expectation of how songs themselves work. We expect the action to end with the song, as it builds to a crescendo, a finale…then it keeps going. Like the car crash, Andrew doesn’t stop, pushing beyond what we (and Fletcher, and the band, and the audience) expected. After such an intense performance, we are denied the smooth transition to a quieter moment and forced into yet another buildup of tension with the solo. The result is that, by the end of it all, the tension’s nearly unbearable, and Andrew’s ultimate victory is an even greater triumph thanks to the false endings that Chazelle throws in as curveballs to disrupt our own sense of tempo.

Narrow Perspective

Our protagonist, Andrew, is a pretty detestable character for much of the film. He berates his classmates, belittles and antagonizes his family members, and treats his girlfriend like shit before breaking up with her because she’s not “motivated” enough for his liking. If we take away his drumming aspirations, there’s very little that redeems his actions in Whiplash. But Chazelle takes care to sympathize the audience with our protagonist in a few ways.

For one thing, we are placed in Andrew’s shoes from the get-go. The cerebral, claustrophobic shooting techniques seek to create an almost first-person perspective, and we feel every emotion and slight that Andrew does. Every tiny detail that Andrew zeroes in on, we do as well:

We feel the same longing and jealousy that Andrew feels without needing a word of exposition. Not two scenes earlier we got a sequence in which Andrew longs after the cashier at the movie theater, and now he enviously watches his classmate flirt with a bombshell. Furthermore, despite Ryan’s kindness towards him, it establishes a rivalry between them and reason for us to root Andrew on. In fact, Ryan is a saint for basically the entire movie, but Chazelle manages to get us to dislike him anyway by always portraying him as the object of Andrew’s scorn and a major motivator for him to get better.

Andrew’s father, Jim, is also an object of fascination for our hero, but for different reasons. We see this early on when they go to the movies together:

It’s subtle, but we get a glimpse here of how Andrew views his father. After a discussion about keeping one’s options open and tempering expectations, we see Jim apologize to someone else for bumping into him! It’s clear that Andrew not only notices the lack of respect others show for his father, but his father’s seeming lack of respect for himself, and doesn’t want to fall into the same trappings himself. If we are to interpret Jim as a future projection of Andrew, we see how Andrew might fear what he is destined to become, and why he may be incentivized to do things differently than his father did. These tiny moments help to amplify Andrew’s motivations and ambitions and explain his extreme actions later on.

We also get several moments of micro-disrespect towards Andrew that help us enter his mind space even more. Like when he asks his lower-level band instructor for advice:

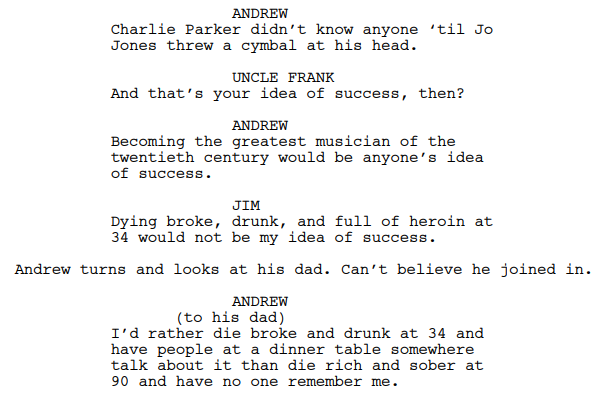

Or in the now-infamous dinner table scene, when Andrew meets with extended family and struggles to express the significance of his accomplishments:

As much as Andrew acts detestably towards his loved ones throughout the film, we also see the way he is treated in return. Like an afterthought. An also-ran. Some cute kid who thinks he can do something useful with a silly hobby. Because we’ve been right there in the trenches with him, we simmer with frustration just as he does at these slights, knowing that these fools just don’t understand how much this means to him. For as esoteric and obscure Andrew’s pursuits are, Chazelle makes it a universal struggle by appealing to the sense that other people don’t respect our passions, something anyone can relate to. It may not excuse all of Andrew’s actions, but it makes us root for him subconsciously.

Then, of course, there’s Fletcher. No matter how terribly Andrew acts throughout the film, he pales in comparison to the monster that is Terrence Fletcher. Chazelle subscribes to the notion that, in order to make a bad person likable, pair them up with someone who is even worse. As we watch Andrew get slapped around, yelled at, insulted, humiliated, and otherwise beaten into the dust by his instructor, we instinctively excuse many of his own outbursts as a reasonable reaction to Fletcher’s abuse. In some ways, Andrew becomes a mini-Fletcher, even using Fletcher’s own words against other people to get what he wants. If we buy into this “bullies beget bullies” mentality, we begin to wonder what Fletcher himself might have gone through to get to where he is, and maybe even sympathize with his actions once we learn the torment he himself endured. Which brings us to…

The Perfect Antagonist

I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again: no protagonist is complete without the equal and opposite force driving him/her forward. A good antagonist isn’t just powerful, he must be a proper match for the character weaknesses inherent to the protagonist, forcing them to change organically. Fletcher is the true foil to Andrew’s character, maneuvering him into difficult choices and exploiting his weaknesses to great effect.

One thing Fletcher is great at is learning his students’ weakness and using it against them. Early on in the film, for example, Fletcher recognizes Andrew’s insecurity about his utterly unremarkable parents:

And then, in Andrew’s greatest moment of vulnerability, Fletcher twists the knife by using this fear against him:

Is it excessive? Yeah. Is it cruel? Yep. Is it effective? Hell yeah. Fletcher’s goal is to strip away Andrew’s ego completely, and he does so by not only humiliating him in front of the band, but by keying in on Andrew’s secret (that he has nothing and no one to be proud of) and forcing it down his throat.

Fletcher also clues in to what drives Andrew forward, and like us, he figures out the reverence/disdain he has towards classmate Ryan Connolly. As such, he introduces a new element to the mix:

As soon as Fletcher gauges that Andrew might be getting too comfortable in his role, he finds the perfect way to undermine him and push him further. Any time the audience feels that Andrew is close to earning acceptance from Fletcher, we are reminded that this is a relentless, manipulative force in Andrew’s life. And Fletcher has a knack for choosing the perfect way to attack Andrew at an angle he wasn’t expecting, to force him into more difficult choices.

Just as Fletcher knows how to turn up the dial to eleven to push Andrew harder, he also knows when to slow down and draw him in close. Another of Andrew’s weaknesses is his desire for Fletcher’s acceptance. Fletcher constantly dangles a carrot in front of Andrew just out of reach, giving him just enough reason to come back even when he is being beaten down. He welcomes Andrew to the band and compares him to Buddy Rich, then throws a chair at his head. He promotes Andrew to core drums, then brings in Ryan as additional competition. He invites Andrew to play in his pro band, then pulls his revenge stunt in front of the entire jazz world. Each successive terrible thing that Fletcher does is preceded by a moment of grace, so that each time we (and Andrew) truly believe we’ve earned his goodwill when that’s far from the case.

Unlike your typical, mustache-twirling supervillain, Fletcher has purpose behind what he does. He isn’t indiscriminately cruel…he truly believes that what he’s doing is right.

Even our protagonist, who has been at the receiving end of Fletcher’s abuse for months, has to admit he has a point. Fletcher goes on to lament the current state of jazz and the back-patting culture of America today: participation trophies and “good jobs” supplanting actual talent and hard work. Whether or not you agree with his philosophy of torment to produce greatness, you must admit that he raises an interesting question and has noble goals, even if his methods are devious.

A Microcosmic Ending

In my mind, Whiplash has one of the greatest endings in cinema history. It encapsulates everything that the movie preceding it has been building towards: a final conflict between the two major forces, a heroic failure and recovery, a tense, action-packed crescendo, and a final victory for our protagonist. But for as intense the moment or the relief afterwards feels, picking apart the layers of the ending yields even more impressive storytelling that requires further analysis.

To begin, we should first examine the film’s opening, which the director intended as a sort of “mini-movie” encompassing the entire film. It includes the same rise-and-fall structure that the entire film does, sets up the stakes, and introduces our characters’ motivations and power dynamics. The ending accomplishes many of the same goals, but it does so with the benefit of context. The opening of the film is our first introduction to Andrew and Fletcher, with no prior history between them or with us. Now that we’re emotionally invested in Andrew’s journey, and we understand the depth of Fletcher’s depravity plus the rationale behind it, we are set up for an emotional roller coaster. It isn’t the first time we’ve seen Andrew stumble, or Fletcher betray his trust, or Andrew get back on the horse, but now that the stakes are raised in front of a massive audience, we yearn for just one more success. It’s a formula as old as the sports film genre, but it’s executed to perfection.

The hidden brilliance of the finale is not Andrew’s journey, but Fletcher’s. As the audience tensely roots Andrew on and zeroes in on his success, as we’ve been groomed to do this whole time, we may not even notice Fletcher’s arc during the scene. He begins gleeful as Andrew fails for perhaps the last time, then falls to worry and anger as Andrew transcends his abuse and rises to greatness. This is where most movies would end: with the hero vanquishing the villain. But Chazelle doesn’t stop there. Fletcher too regains his composure and inserts himself back into the moment:

In the latter half of Andrew’s triumphant solo, Fletcher regains control, guiding Andrew through the motions, and Andrew is happy to comply. And it’s at this moment that we begin to question whether Andrew’s victory is truly a victory after all. His journey, after all, has involved breaking free of Fletcher’s evil influence, but here he is, willingly returning to his tormentor’s clutches. It also becomes clear upon further review of the film as a whole that Andrew’s idea of success might look different than the audience’s:

In order to achieve the greatness he desired, we have seen what it cost Andrew: friends, family, love, and any sense of self-worth he once clung to. He’s given in to Fletcher’s commands in order to reach the pinnacle, and if his own predictions (and Chazelle’s) hold true, he’ll die alone at a young age. Is that a tragedy? Well, if Andrew’s name makes it to dinner tables everywhere in the decades to come, perhaps not.

This also highlights the most crucial aspect of the screenplay by far: Andrew and Fletcher are competing for the same goal. We can’t call this a total success or failure for either of them because, ultimately, they both got what they wanted. Andrew achieved greatness, and Fletcher created the star pupil he always craved. We sorta knew this already, as evidenced by how easily Andrew takes to Fletcher’s philosophy, but it has only become clear now, at the very end, when both of them relish in the triumph together. Our final shot sequence sees Andrew look to Fletcher for acceptance, and Fletcher giving it to him. They share a smile, the finale ends, and credits roll. What a ride.

Conclusion

Whiplash is a stunning experience, one of the few times in my life that I left the theater in a daze, thoroughly immersed. It stuck with me long afterwards, festering in my mind for weeks, months, years. It’s such a simple story, stripped to the bare bones of what it’s trying to say, but every moment is chosen for maximum impact and resonance. It asks relevant questions to today’s society about what it means to achieve success and what lengths are acceptable to go get it. And its ambiguous finale, both gripping and thought-provoking, lingers long after the curtains go down. Depending on what you believe about reaching greatness, you might agree or disagree with Fletcher’s methods, and that’s all you can ask of a great villain.

VERDICT: A+

Thus concludes my Five Faves series! What is your favorite film of the bunch? Which films make up your pantheon of greats?

-AD

All image rights belong to Sony Pictures Classics.

Other Five Faves entries:

- Pulp Fiction (1995)

- In Bruges (2008)

- The Dark Knight (2008)

- The Social Network (2010)

19 thoughts on “Five Faves #5: “Whiplash” (2014)”