Welcome to entry #4 in my Five Faves series, chronicling my five favorite films of all time! We’ve already discussed Pulp Fiction, In Bruges, and The Dark Knight, and today we’re looking at Aaron Sorkin and David Fincher’s collaborative masterpiece, The Social Network (2010). The biopic based on the book by Ben Mezrich follows a young Mark Zuckerberg at Harvard as he builds Facebook from the ground up, and the resulting personal and legal drama with both his friends and rivals.

At first glance, some may find it strange that a story involving two legal disputes, a bunch of technical and financial jargon, and no discernable structure could be one of the most engaging dramas of the past decade. But Aaron Sorkin works his magic to craft a tense, gripping experience thanks to a few weird tricks. (Directors HATE him! You won’t believe #12!!!) Clickbait aside, let’s dive deeper into the script of The Social Network and try to make some sense of the madness…

Quick-Fire Exchanges

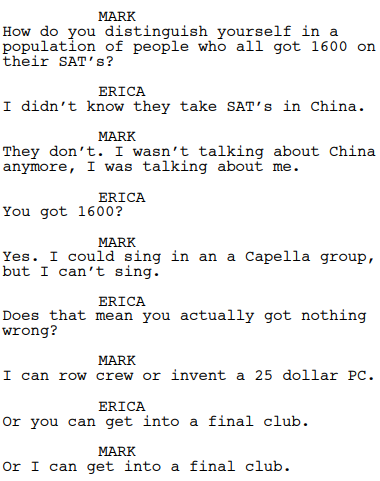

Sorkin is known for rapid dialogue and frenetic pacing, and while that’s earned him some mockery over the years, his rapid-fire style complements this film nicely. One of the ways Sorkin creates tension within his scenes is by having his characters not on the same page at all times…often our characters are just as lost as the audience is. The opening scene, Mark and Erica’s dinner date, is a perfect example of this:

The film opens with an over five-minute conversation between two people with no visual stimuli whatsoever. Why does the scene work so well? Mark and Erica’s relationship is strained, and we start to get a sense of why just from their dialogue. They are not on the same wavelength most of the time, with Mark’s mind running a million miles an hour while Erica attempts to stop and dig deeper into each point he makes, which results in her lagging far behind his meandering train of thought. He starts talking about China, then SAT’s, then by the time Erica is asking about China he’s on to a capella, then by the time she gets to SAT’s he’s on to rowing crew, and so on. This charade continues almost the entire time, culminating in Erica leaving the relationship because it’s too exhausting to keep up with Mark. Not only does the content of Mark’s dialogue inform his character, but the structure of his conversations does so as well.

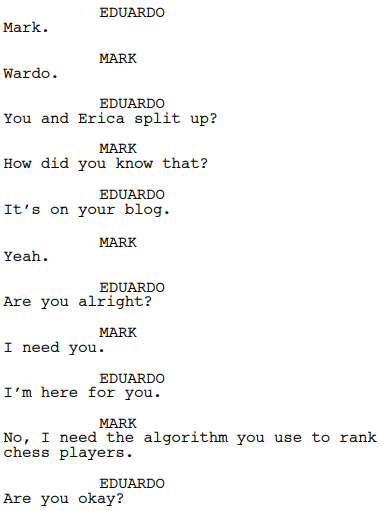

We see a similar dynamic in play when we first meet Mark’s best friend Eduardo:

This exchange is played for humor, but it again reflects the fact that Mark is miles ahead of his peers. Eduardo’s sole focus to begin the scene is to see if his friend is okay after his bitter breakup, but Mark is already on to bigger and better things, i.e. building the FaceMash website. Sorkin accomplishes three important things with this style: 1) Character traits are brought out naturally through disparate dialogue; 2) scenes have built-in tension that keep us engaged; and 3) the quick pace keeps things refreshing even when information is being hurled at us.

When I wrote about Pulp Fiction, I talked about how Tarantino uses delayed payoffs to generate tension, pushing back the resolution of problems as far as possible to make the audience sweat. Sorkin does something similar: with his barrage of quick dialogue, he creates diversions and detours in order to distract us and the characters from easy answers.

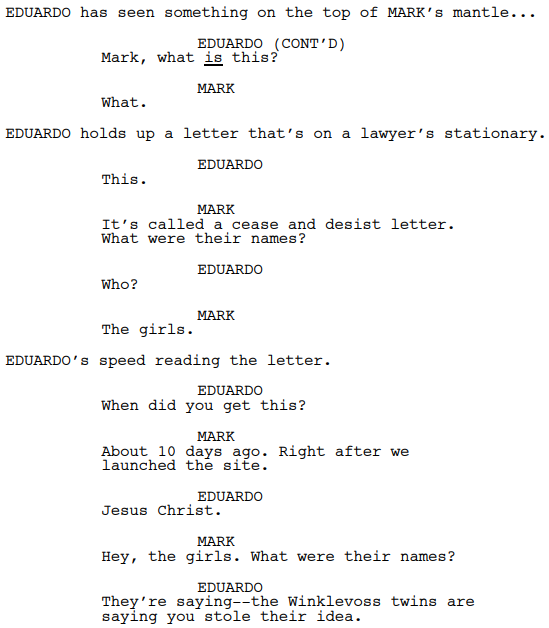

Again the characters are on totally different pages here. Eduardo is suddenly worried about the letter, while Mark is totally unconcerned and trying to turn the conversation back to the girls. This is also the first the audience has learned about the cease-and-desist order, so we, like Eduardo, are frustrated by Mark’s attempts to change the subject as we try to learn more.

Diversion Tactics

The subject matter of the film is often pretty dry. A lot happens, and not all of it is visually-stimulating, so Sorkin has to work some magic a few times to keep us entertained. I’ve talked in the past about how shows like Game of Thrones or films like The Big Short hide their exposition dumps behind flashy visuals (ie. sex scenes) in order to provide some eye candy during the boring sequences. Sorkin doesn’t quite stoop to that level, but he does still find ways to sneak in exposition without totally losing us.

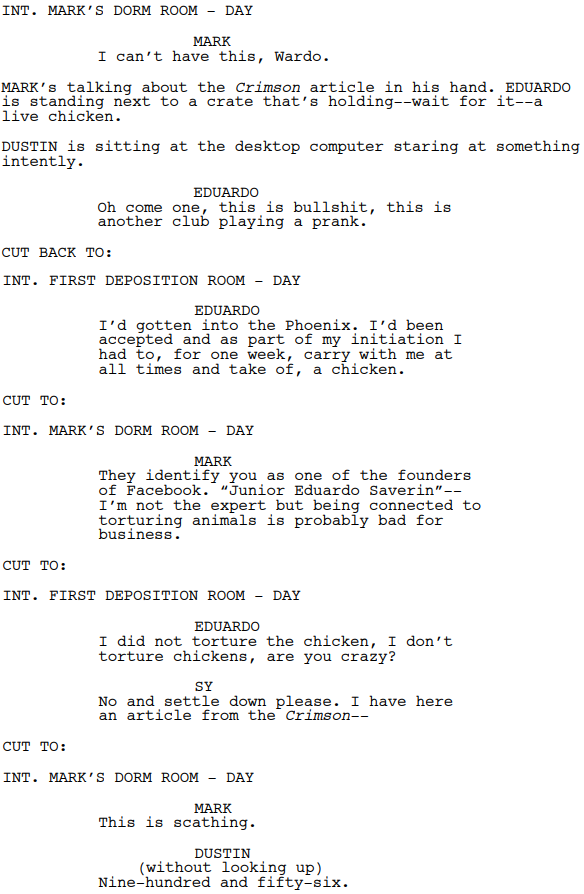

Consider the scene where Eduardo’s animal cruelty accusation is brought up in court:

What would normally be a rather dry exposition sequence is spruced up in two key ways. One, as we’ve been doing all throughout the film, we’re cutting back and forth between the deposition and actual events. And two, we have another character, Dustin, doing a countdown with no explanation. We’re now not only trying to keep up with the rapid-fire exchange between Mark and Eduardo, and not only following the frequent cuts back to the deposition room, but also wondering what Dustin is doing. This adds an additional layer of tension by posing questions that we want answered, and once the question of the countdown is answered (reaching the 150,000 subscriber milestone) we realize how this microcosmic argument ties into the bigger picture.

Sorkin also uses this technique to accomplish multiple things within the same scene. Consider the scene in which Tyler, Cameron, and Divya realize they’ve been swindled:

All three characters are doing different things! Tyler’s learning about the Facebook website, Divya’s trying to reach Mark, and Cameron’s contacting the family lawyers. This could have been done across three separate scenes, but Sorkin jams them all together so they happen simultaneously. He’s able to both cram exposition into a compact space and make dull sequences exciting.

One of the more famous examples of this tactic comes when Eduardo gets an angry phone call from Mark while his girlfriend Christy is visiting:

This scene could have worked fine with just the phone call argument…the content of the conversation is emotionally-loaded already. But Sorkin doesn’t stop there. He includes the Silicon Valley party in the background of Mark’s end of the call, and Christy’s psychotic behavior at the other end. This combines two different elements of tension into one and ratchets up the intensity even further on our characters. We are put into Eduardo’s shoes and feel the same pressure he does, so this moment of conflict is amplified by a third party’s interference (similar to Dustin’s countdown in an earlier scene). The second half of the film sees Mark and Eduardo dealing with the same personal pressures as before but now with real world implications complicating matters as Facebook grows exponentially. Sorkin reflects this by not allowing characters to tackle problems one at a time, forcing them to multitask and juggle all sorts of different issues at once. This is a happy marriage of form and function, both creating tension for the characters and accurately portraying their struggles at that point in time.

Visual Flair

I don’t want to take anything away from David Fincher, who certainly applies his own distinct style to The Social Network. But just from reading Sorkin’s script, you get a vivid picture of what’s happening without needing the visual reminder of the film. His descriptors, an often-underrated aspect of the screenplay, ooze with flavor and tell us everything we need to know about our characters and settings up front.

Consider a few character introductions:

So many average screenwriters just describe their characters’ general appearance. “Average-looking guy with messy hair.” “Pretty girl with a big rack.” It’s the kind of thing that doesn’t appear on the screen, so a common mistake is for writers to just skimp on this aspect of the script and focus on the parts that will actually be seen by the audience (the dialogue). Sorkin takes things a step further and gives characters a distinctive trait: Mark’s fashion apathy; Erica’s naive politeness; the Winklevoss’s self-aware supremacy. We feel like we know these characters immediately just from the two or three lines we get to introduce them. I love the way that Sorkin not only describes the characters’ appearance, but lets us know what we should expect from them behaviorally in the future.

Even the settings themselves are handled with great care.

We don’t even need to see the final film to understand the tone of the room. As contrasted with the flashy, sleek finals club parties at the beginning of the story, the sorts of parties that our heroes indulge in are lame knock-offs. Again, Fincher does a masterful job in translating this to the screen, but Sorkin lays the foundation by capturing the essential qualities we need to glean from the moment.

To further this goal, Sorkin sometimes includes little tips and reminders for the director and the set designers. He’s not interested in the specific, meticulous look of the shot, but moreso in the tone being conveyed:

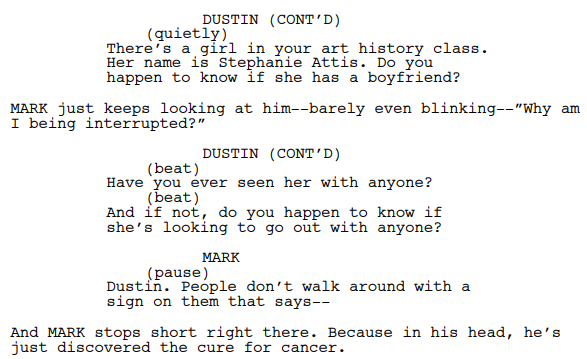

Even characters’ thoughts are often depicted in the descriptors, usually a no-no. Again, Sorkin includes these to help the actors know what sort of emoting they ought to do in order to portray the characters’ mood during a scene.

Sorkin is a master at capturing the essence of a moment. He writes just enough to perfectly encapsulate what the audience should take away from the scene without overstepping his bounds and doing the director’s job for him. Again, I don’t mean to detract from the job David Fincher did, but Sorkin gave him the perfect alley-oop to finish the slam dunk.

Hidden Structure

The odd thing about The Social Network is that it does not contain a traditional plot structure. No hero’s journey, no three acts, nothing like you’d expect to see from a formulaic Hollywood screenplay. And in some ways, it’s because the source material has no discernable structure either. You can trace the origins of Facebook to one or two key moments, but the story of the website hasn’t yet finished. How do you craft a beginning, middle, and end out of an open-ended story?

To answer this question, I first want to talk about another of Sorkin’s films, last year’s Molly’s Game. If you have followed my blog in the past, you might remember that I did not enjoy that film, which may surprise people. After all, it uses many of the same techniques that he uses in The Social Network: rapid dialogue, a hyper-intelligent protagonist, and a legal case pertaining to the main action. I felt like Sorkin was mis-applying these techniques to that story, however; Molly doesn’t share the same neurotic behavior as Mark, and her story is far more open-and-shut as well (her games got shut down, providing a concrete ending). Your technique should match your specific character and story, and here, it certainly does so.

The dueling court cases (Mark vs. Eduardo and Mark vs. the Winklevosses) and out-of-sequence storytelling works because, again, it develops more tension. We begin the film seeing Mark and Eduardo’s friendly relationship, then abruptly cut to three years later when Eduardo is suing Mark for hundreds of millions. The audience immediately asks the question: why? I’ve talked so often about the importance of posing questions to the audience to make them active participants in the narrative. When a nonlinear narrative is done correctly, this is the result: presenting information in such a way that we attempt to put the pieces together ourselves. Therefore, we know what to look for in future scenes and even in past scenes with the benefit of hindsight.

The film is book-ended by Erica, a girl who has little relevance to the main plot. The first thing we see is her breaking up with Mark, and the last thing we see is Mark attempting to reconnect with her. Considering how crucial it is to start a film at the exact appropriate moment, it’s clear that this is a deliberate choice by Sorkin and a key motivator for Mark. By setting Erica as the foundation of the film, we understand that the film is an exploration of Mark’s insecurity and acceptance. The relationship between Mark and Eduardo may be the central focus of the film at large, but Erica’s inclusion in the plot is a clue that the story is a parable of sorts, with one crucial aspect of Mark’s personality under examination: his difficulty in connecting with people, and his desire to be loved above all else.

Conclusion

The Social Network is the rare screenplay that reads just as well as it appears on screen. Like a play, all of the key moments of action and characterization are contained within the intricate dialogue. Sorkin manages to take a rather bland subject matter and infuse it with drama and intrigue. And that’s to say nothing of the killer score by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross, the flawless acting of Eisenberg, Garfield, Timberlake and more, or the immaculate screen direction of the legendary David Fincher. Everything comes together for a beautiful experience that continues to surprise and enthrall me with each subsequent rewatch.

VERDICT: A+

All script and image rights belong to Columbia Pictures.

Other Five Faves entries:

- Pulp Fiction (1994)

- The Dark Knight (2008)

- In Bruges (2008)

- Whiplash (2014)

7 thoughts on “Five Faves #4: “The Social Network” (2010)”