Whenever I tell friends and family about my passion for film, the first question I invariably get back is, “What is your favorite movie of all time?” And as any cinephile (or scriptophile!) knows, it’s a hard question to answer. My tastes change from year to year…hell, from day to day! Sometimes my top film will change every time I re-watch something else high on my list. Regardless, I have put serious effort into answering this question for myself in recent months, and while I still can’t pinpoint a singular title, I have narrowed my list down to five. These are the five films that rotate in an out of my top spot on any given day, jockeying with one another for supremacy yet still a notch above any other film below them. This new series will explore each of the five titles and dissect their screenplays to examine what makes them so special, starting with Quentin Tarantino’s masterpiece, Pulp Fiction (1994).

DISCLAIMERS: I am not claiming that these are the five greatest films of all time, just my favorites (not to say that they aren’t great films in their own right). They will all tend towards the past couple decades, and I acknowledge the recency bias. I have great respect for cinema’s long history even though older titles with greater acclaim don’t speak to me as much as these newer entries into the lexicon did. My favorites might not match your favorites, and that’s okay. I hope this series will shed some light on what I look for in a film and what qualities I value more highly than others, which most of the time pertains to the screenplay. Also, this Top 5 is not in any particular order…the fact that Pulp Fiction is being discussed first does not automatically make it #5 or #1. At various times it might occupy one of those spots, but the only fair way for me to order these films is at random.

Tangential Character Development

There are so many iconic characters in Tarantino’s screenplays, each with their own distinctive personality traits and mannerisms. But what I love about Pulp Fiction is how he creates these character identities through indirect association. Some have complained that the dialogue of the film is inane and pointless. I disagree wholeheartedly…while the conversations between characters may seem random at times, they are actually carefully constructed to shed light on characters without being too on the nose.

Consider the introductory scene, a nearly ten-minute conversation between Vincent and Jules. We learn so much about these two men without ever needing to be told what we are supposed to think about them. Vincent appears enamored with his recent trip to Amsterdam and the foreign culture he experienced. The most infamous exchange in the film centers on this cultural disparity:

Vincent’s romanticism of these foreign quirks suggests that he has a counterculture streak. We also get hints of his anti-authoritarian sentiments with his discussion of hash bars and police search procedures. All of this is conveyed in a simple, throwaway discussion about McDonald’s. The payoff for these minor reveals will come much later in the film, but the seeds have been sewn here before we ever see Vincent make a single character decision.

Some time later, he and Jules discuss the significance of a foot massage:

This exchange accomplishes two important goals. One, it sets up the conflict and tension of Vincent’s upcoming date with Mia Wallace by establishing the stakes of him overstepping his bounds. But two, it highlights Jules’s own personality: he takes pride in the principle of things, and he’s willing to go to war over semantics. Jules lives his life by a strict set of guidelines with a strong opinion of how the world works. We see the same thing crop up later in a discussion about pork:

Jules’s behaviors, however ridiculous, are defined by his rigid view of how things are. He classifies certain animals as “filthy” with his own rubric of what qualifies as such. Vincent in turn frequently pokes and prods at his arguments, pointing out holes in his logic, and while Jules is open-minded about his points, he remains steadfast in his resolve. Again, we get a delayed payoff at the end of the film during the standoff with Pumpkin and Honey Bunny, as he reasons through letting them live thanks to his unique predetermined perspective on life. Even his mis-reciting of the famous Bible passage reinforces this point: he lives his life by a strong yet errant moral compass, not always making sense to others but at least to himself.

Delayed Payoffs

The nonlinear narrative and meandering dialogue of Pulp Fiction isn’t just a random decision…it enhances its emotional ebbs and flows, building tension and subverting expectations at every step. Every twist and turn of the film is carefully chosen by Tarantino in order to squeeze as much tension and emotional impact out of every scene.

Vincent’s date with Mia Wallace is a good example of this. We’ve previously established that Marsellus Wallace is a man to be feared, so it makes sense to us why Vincent is walking on eggshells around this beautiful, impulsive woman. Vincent just wants the night to be over quickly, which makes Mia’s prolonging of the evening (making Vincent wait while she gets ready, insisting on eating at the 50’s diner, volunteering them for the dance contest, and so on) that much more excruciating. Their conversation at the diner is constantly interrupted and broken up, by the waiter or a bathroom break or something else…much like the film as a whole is fragmented into pieces. Mia mentions a one-liner she delivered on her TV pilot on page 35, but we don’t hear the punchline until page 56. This kind of delay is indicative of the way Tarantino builds tension into his screenplay by elongating moments and preventing them from reaching climax in prompt fashion.

This technique is especially apparent after Mia OD’s on heroin. Again, the resolution to the problem takes relative ages (10 whole pages), and every bumbling move and delay from Vincent and the others is strongly felt:

This sort of screwball, Abbot-and-Costello, back and forth comedy style would be amusing if there wasn’t a girl near death lying in the next room over. In fact, it was kinda funny when we saw Vincent interacting with Lance and his wife in an earlier scene, but in present circumstances it ratchets up the intensity of the moment to near-unbearable levels.

Tarantino also utilizes situational irony to great effect in the film. There’s a common film trope known as the “bomb under the table” theory, popularized by Alfred Hitchcock, in which you show a catastrophic event about to happen (ie. a literal bomb under a table) then ignore it for a while, letting the scene play out and making the audience sweat it out, thereby raising the stakes. Tarantino has used this technique to build tension in several of his films; for instance, in 2009’s Inglourious Basterds, halfway through the pleasant opening conversation between SS Agent Landa and the French farmer, we pan down and see the Jewish family hiding underneath the floorboards, a perfect application of the theory.

In Pulp Fiction, Tarantino puts his own unique spin on the technique thanks to the nonlinear narrative. The first chapter sees Vincent and Jules execute Brett in his apartment just before we fade to black. After a big jump forward in time for the second chapter, the third chapter picks up where the first leaves off, but with a twist. We see a previously-unseen tenant in the bathroom next door, wielding a massive gun. This retroactively applies tension to the earlier scene, and suddenly the audience is more invested than they were before in what happens next. Because of the time delay between these scenes, we are invited to look back farther in time to remember the context, making us active participants in the narrative.

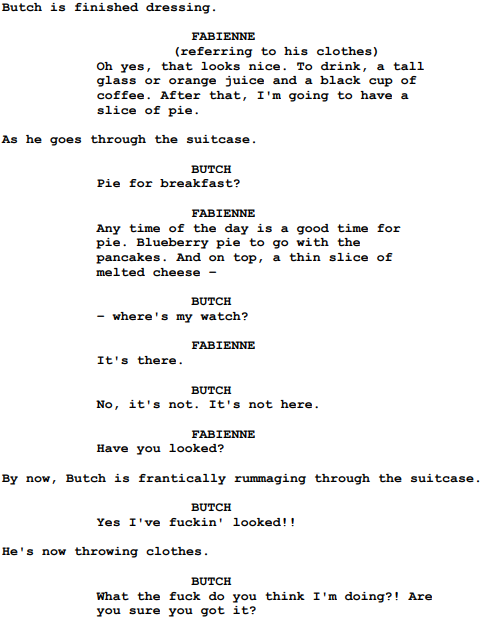

The vignette structure allows Tarantino to mask these setups well. The flashback sequence involving a young Butch hearing the story about the Gold Watch is presented without context, so the audience isn’t sure what to make of it. But given the odd out-of-sequence format, we just assume it’s another in a line of random, unrelated events. But then later, when Butch and Fabienne are packing to skip town, we get this payoff:

Without the context of the prior scene, we just see Butch flipping out for no reason about some watch. But now that we know the importance it holds to him as a family heirloom, there’s a newfound terror to the scene: we know that Fabienne fucked up big time. We are finally paid off by the setup in the flashback.

The cumulative effect of this is the two bookends of the film: the opening and closing scenes, both featuring Pumpkin and Honey-Bunny robbing the diner. In the first scene we have no context: just two nameless kids making an impulsive decision. By the final scene we again get a bomb-under-the-table moment when we discover that Vincent and Jules are also present in the diner, and suddenly we have more at stake when we realize that, despite the nonlinear narrative, we never saw Jules in Act II and don’t know what becomes of him. The ultimate delayed payoff comes here as the stickup that begins on page 6 doesn’t occur until page 117, over two hours later. The fact that Tarantino begins and ends his film with this moment points to the overall theme of the film: stretching a moment to its absolute limits, even chopping it up if necessary, in order to maximize the dramatic impact on the audience.

Mass Entertainment and Passive Protagonism

Tarantino is well-known for his frequent throwbacks to an earlier age of cinema, sometimes to a fault. All of his early films are loaded to the brim with homage and nostalgia to an older era of entertainment, not just of film but television, comics and music as well. Pulp Fiction is well-known for how much referential imagery it contains, and the world is often just as vibrant as the characters within it. Much like reality, Tarantino’s characters are shaped by the entertainment around them, and this motif of heavy nostalgia is actually a clever way of bringing out characterization. Our characters are mainly passive protagonists, in the sense that they are shaped by the world around them and react to things rather than proactively setting events in motion.

Take the famous Jack Rabbit Slim’s diner scene for instance. The entire building is an homage to 50’s entertainment: Buddy Holly mingling with Marilyn Monroe as Ed Sullivan introduces Chuck Berry songs. But Tarantino doesn’t just throw these references at the wall in the hopes that something will stick with the audience. The way Mia and Vincent interact with the environment informs their characters. Mia is enamored with the flashy imagery and uses it as an escape, reinforcing her impulsivity and tenuous relationship with reality, whereas Vincent is jaded with the cultural bombardment as his disdain for mainstream sentimentality resurfaces. There is never a moment where these characters outright say something contrived like, “I love this place, it distracts me from my listless life” or “this place is everything I hate about the world”…we have to draw inferences about their characters based on their reactions to the place.

Vincent’s distrust of media has a lot to do with the journey he goes through during the film. He and Jules have to deal with lots of unexpected setbacks, and their entire journey is shaped by bad things happening to them, not because of them. The kid hidden in the bathroom that barges out and shoots at them. Marvin being accidentally shot in the face. The Bonnie Situation. The diner stickup. Mia OD’ing on heroin. Butch finding Vincent’s machine gun on his counter. There’s a running joke among fans of the film that every time Vincent goes to the bathroom and reads his book, something bad happens. This is an intentional choice by Tarantino: it implies that the characters letting their guard down for even a moment (perhaps by succumbing to cheap entertainment) can result in disaster. As such, Vincent does his best to resist the allure.

Butch has his own unique perspective on entertainment (and by extension, the world). He seems to have a latent distrust of mass media, reflecting his distrust of the world. When his girlfriend Fabienne watches TV as he sleeps, for instance, he asks her to turn it off. Interestingly, Butch is the only one of the three main characters who can be classified as an “active” protagonist…he imposes his will upon the plot by refusing to take a dive in the fight and killing the other boxer. As such, he rejects the notion of imbibing constant entertainment and passively letting the world come to him. He is able to get the upper hand over Vincent because the gangster was reading in the bathroom and not paying attention. But when Butch’s fortunes turn south and Marsellus Wallace spots him in the street, it’s after he sings along to a song on the radio: putting his guard down for only a moment, allowing the creep of entertainment to distract him. And once Butch frees himself from the rapists, he again reveals his true character by taking further action, returning to free Marsellus. Tarantino seems to suggest that in order to thrive and remain active in this world, one must reject the numerous distractions that entertainment provides.

Even the narrative structure of the film itself is a throwback to an old-school form of cheap entertainment. The title takes its name from “pulp” magazines, fictional tales printed on pulp paper with quick vignettes designed for low-brow entertainment. Even the film poster (seen above) is designed to look like a magazine cover! Tarantino suggests that the numerous sub-chapters of the film are meant to mimic this style. Some see this as a cop-out, a crutch used by Tarantino to excuse the film’s quality in calling back to a looked-down-upon medium. To me, not only does this decision provide nostalgic value for older viewers who might remember those days, but it adds structure to an otherwise-pointless and nihilistic story, as if to say, “even if this doesn’t resonate with you, at least it entertained you.” It’s not to say that Tarantino doesn’t go overboard with his homages sometimes, but in this case, he successfully marries form and function by borrowing a bygone medium to add weight to his own tall tale.

Conclusion

I’m surely not the only late-teen/early-20’s white male who fell in love with Pulp Fiction in my formative film years, and it seems to continue appealing to that demographic (and others) even two and a half decades later. Underneath the witty banter, spectacular violence, and glitzy homages is something universal…some connecting thread that makes it so beloved. The cleverly and carefully-constructed screenplay is perhaps my favorite of all-time; every time I watch the film or read the screenplay I discover new little gold nuggets, clues and setups for future events. All of this is wrapped up in endlessly-quotable and memorable dialogue, making conversations about cheeseburgers some of the most resonant lines in American cinema. There is no film quite like Pulp Fiction, and it will remain one of my all-time favorites until the day I die.

Keep your eyes open for my second installment in my Five Faves series. I will not be revealing my full list otoday, so you’ll have to wait for my next analysis to learn what the other films are. However, I will spoil one of them today, because it’s a film I’ve already discussed on this blog (recently, in fact): The Dark Knight (2008)! I’m as of yet undecided whether that post will retroactively become part of this series or if I’ll write about it again, but that film absolutely deserves a spot in my Top 5.

Next week I’ll be talking about the third film on my list! Any guesses what it might be?

-AD

All image rights belong to Miramax. Script excerpts courtesy of Script Slug.

Other Five Faves entries:

- In Bruges (2008)

- The Dark Knight (2008)

- The Social Network (2010)

- Whiplash (2014)

7 thoughts on “Five Faves #1: “Pulp Fiction” (1994)”