BlacKkKlansman is the latest Spike Lee joint, starring John David Washington (son of Denzel), Adam Driver (son of Han Solo), and Topher Grace (son of Red Forman) among others. It tells the true story of a black police detective, Ron Stallworth, as he infiltrates the local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan by posing as a white supremacist. It has been hailed as one of Lee’s best films since his breakout Do the Right Thing in 1989. Does it live up to such lofty expectations? *SPOILERS AHEAD!*

I like to be well-informed about films and filmmakers before walking into a theater, so I’m embarrassed to say that I am not very well-versed in Spike’s body of work. I saw Do the Right Thing many moons ago, before I was old enough to grasp its socioeconomic importance, but besides that, all I know about Spike is that he is an eclectic, nontraditional filmmaker with a propensity for telling powerful stories about the modern-day black experience. And he goes for the jugular with this film; his period biopic is just as relevant to today’s society as just about any film made in the past decade. It uses the underground Klan and the rise of David Duke as a blatant metaphor for today’s political climate, with the rise of Donald Trump empowering the marginalized white supremacist to rise up as they did in Charlottesville one year ago. I’m going to tread extremely lightly here, since a) I am a white man myself and b) I try to keep my personal politics out of my artistic critique, but it should be noted that, if nothing else, BlacKkKlansman is an important and biting commentary on modern race relations.

But since this is a screenwriting blog above all else, let’s set all that aside for the moment and talk about the craft of the film. Because there are some glaring issues here.

We should start with the characters. Our protagonist, Ron, is a driven young black man who decides that the best way for him to make lasting social change is from within the police department. Regardless of the other characters, I was impressed with Ron’s characterization in this film for a number of reasons. Spike could have gone the obvious route with Ron, having him the sole bastion of justice in a corrupt system, but not only are some of the other officers on the force decent men, but Ron himself suffers a crisis of faith that he must reconcile within himself. Ron becomes romantically involved with Patrice, a black activist, who argues that all cops are pigs and the system is so corrupt that it cannot be reformed (and must therefore be overthrown). Ron starts the film disagreeing with her, justifying his position on the force to himself as much as to her, but as time goes on and he sees just how fucked everything really is, he begins to wonder if she has a point and if violence really is the only answer. This question ever-gnawing at Ron’s conscience was fascinating to watch played out, and definitely the highlight of the characters.

It’s essentially every other character in the film that I take issue with. Now again, Spike Lee is making a very clear statement with this film: white supremacy is unequivocally evil and non-nuanced. In fact, he includes the infamous Trump speech (“violence on both sides”) later in the film to highlight this notion. There is no moral salvation for David Duke or any of the other KKK members, and as an artistic statement that’s powerful, but as a film it’s frankly kinda boring. Characters are supposed to be about change, and none of the other characters besides Ron do much changing. They are transparently evil to begin with, and just as much (if not more) by the end. It’s difficult to criticize this because clearly it was an intentional move on Spike’s part, and his message seems to be that the enfranchised white characters are set in their ways while the burden of choice lies with the black characters: act or stand by?

This becomes even more problematic when considering the white members of the police force. You have the one blatant racist who gives Ron and the other black characters shit all film, but there are some decent folk on the force who help Ron with his quest. Adam Driver’s character in particular (Flip Zimmerman) is not a “real” white man, but a Jewish man. Flip could easily have been labeled a “white savior” for the film, given that he does much of the dirty work and arguably saves the black characters from a terrible fate, but Spike Lee emphasizes his “true” identity to assure us that this is still a story about minorities upsetting the established order.

Herein lies the problem: Flip is able to easily tap into his racist side, spewing epithets and nearly committing acts of violence towards black men and women. And when shit hits the fan, nothing bad happens to him! He’s able to return to his previous state with no change. Where is his crisis of faith? I was waiting for a moment where he has to make a tough decision between honoring his heritage or keeping his cover with the Klan, but it never came. The closest it came was the scene where they ask to look at his dick to see if it’s circumcised, but the scene is interrupted and they never revisit it. What the hell? Let someone other than Ron make a hard decision! And before you get angry that I want the white guy to have his moment of glory too, keep in mind that by Spike’s own logic this is a Jew moreso than a white man, so yeah, you’re damn right I wanted him to get his due and fulfill his character setup.

Let’s talk about the plot next. Now this is a true story, so it’s not like there’s a lot of leeway to change things willy-nilly, but the good news is that this is already a super-compelling story with the potential for tons of situational tension. Which begs the question: why does all the tension in the film feel flat and deflated before it can even begin?

A couple examples. One scene finds the real Ron Stallworth accepting a phone call from the Klan just as the fake Ron (Flip) arrives for a Klan meeting, unawares. This is a great setup for a tense moment that never comes: we soon learn that these two instances are not concurrent, and Flip’s arrival was in fact some greater time period later. What a major blue-ball! Later in the film, a Klansman recognizes Flip as a cop during a meeting with David Duke, and Felix (another Klansman) puts together the deception with the real Ron Stallworth. Again, great setup for a moment of intense dramatic irony…and it goes absolutely nowhere! The big reveal is glossed over before Felix runs off to get himself killed, and nothing more comes of it! WTF?! So many wasted opportunities to make the audience squirm and sweat for our heroes’ survival.

It’s pretty difficult to put a definitive genre on this film. Is it a drama? A comedy? A crime thriller? A political critique? A historical biopic? A buddy cop romp? A social satire? Spike Lee subverts all our expectations by muddying the waters between these delineations, which at times makes the film tonally incoherent. There are moments of big laughs (pretty much every phone call between Ron and David Duke was a hoot), political/philosophical debates (Ron and Patrice’s dates), and half-assed thrills (the aforementioned awkward situations and other similarly-deflated tense moments). The trailers set this film up as a drama with a biting, satirical edge to it, and I’m not sure that that’s what we got. It felt like one giant homage; everything was a metaphor for everything else and nothing is meant to be taken at face value. I’m not saying films can’t do this (one of my favorite films of all time does this very well), but when you have to sacrifice character arcs and narrative tension to make your statement, it’s jarring and non-conducive to a fulfilling cinematic experience.

To be fair, not all of the setups go without payoffs. The best comedic scene comes in the final conversation between Ron and Duke over the phone, but the setup comes much earlier, in one of their first conversations. Duke describes how he can recognize a white vs. black voice based on word pronunciations, such as the word “are” (which he believes black folk pronounce as “are-uh”). Ron throws it back in his face when, as Duke insists that he’s talking to a white man, Ron replies “Are-uh you sure about that?” Lob and dunk, well done. Some moments of tension are also explored with the disconnect between voice-Ron and in person-Ron. The real Ron mentions over the phone that his father lives in El Paso, so when Flip mistakenly says Dallas during a Klan meeting, we feel afraid and root for him to right the ship. That’s an example of a setup and payoff working together to create natural tension. These moments are few and far-between, and I fear many more missing punchlines became victims of an already-too-long runtime. As with Boots Riley, Spike seems to have tried cramming as much as he could into the film rather than focusing on just a handful of topics and doing the best service to them as possible.

Spike Lee uses several moments in the film to draw homage to past cinema and its relation to modern black experience. The film opens with a recreation of the famous opener of Gone with the Wind, which draws a parallel with the vast suffering of the Civil War and the Confederate flag uniting them. That film was well-known for its poor portrayal of slavery and black Americans, and Spike’s film has a recurring theme of mass media influencing dangerous behaviors and mindsets. To that end, Birth of a Nation features prominently in the middle of the film, as D.W. Griffith’s masterpiece of a silent film is used as KKK propaganda. An early scene with the hilarious Alec Baldwin imitates the anti-black propaganda films put out by white supremacist groups around this time, using moral justification for the inferiority of the African race. Spike also draws homage to blaxploitation films of the 1970’s, playing with lens filters and poster overlays during Ron and Patrice’s scenes for a retro-throwback vibe. It’s clear that Spike has a passion for cinema’s long history of mistreatment of his people, and never misses a moment to remind the audience that what we’re doing at this moment (sitting in a theater, passively watching) is one of the easiest ways to ignore real societal problems lurking underneath the surface.

When it comes to creative direction, Spike Lee is in a world of his own, infusing his films with unique and sometimes revolutionary techniques. We get the infamous dolly tracking shot later in the film, one of his favorite subversive elements to draw attention to the form, but in almost every other facet of BlacKkKlansman, his quirky efforts don’t work for me. The soundtrack only adds to the confusion surrounding tension and genre; a film score should serve as a guide for the audience, helping us understand at what moments we should feel at ease, or scared, or vindicated. The music didn’t really do any of that; it was consistent throughout the film, irregardless of what was happening on-screen, giving every scene a quality of sameness even when they probably shouldn’t.

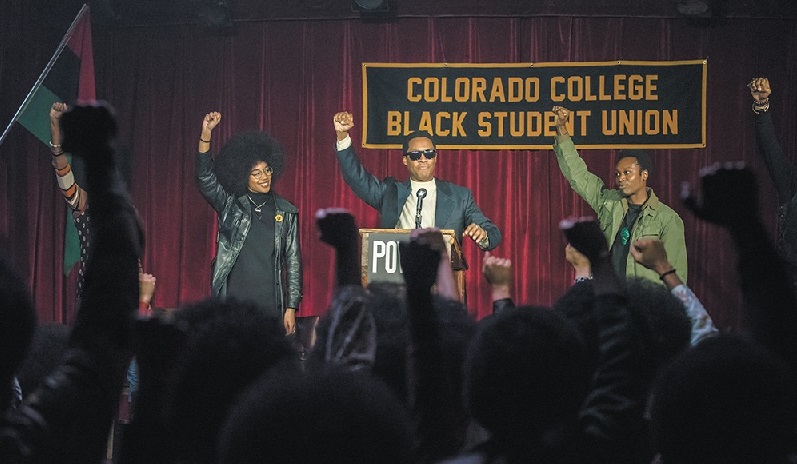

The editing was frenetic and overbearing at times; we would occasionally repeat the same action multiple times from different angles for emphasis. Like when Ron meets some of the officers, we catch the same handshake two or three times. That’s not to say it was all bad, though: the split screen effects during the Stallworth-Duke phone calls were fine, and a good example of visual flair without detracting from the main scene (in fact highlighting the intended tone well). Another early scene, in which black community members attend a civil rights rally hosted by Kwame Ture, plays with lightning in unique ways, framing every member of the audience in darkness and sometimes overlaying them with one another, with beautiful results. Some of the scene transitions are even a bit jarring: for instance, we get a smash-cut pulling us away from a lively black nightclub back to the clinical white police office. Again, no doubt a deliberate choice to juxtapose the two locales, but one that leaves the audience feeling unfulfilled. If that’s Spike Lee’s intent, I congratulate him on his emotional manipulation even though I disagree with the practice in filmmaking.

A brief note on acting: John David Washington did not impress me much, I’m sorry to say. His demeanor is flat throughout the film, largely by design, but even in moments where Ron is supposed to have a big emotional outburst it feels restrained somehow. Adam Driver is great; he can flip the switch between mild-mannered ally to vitriol-spewing monster in an instant, to an almost scary degree. And let’s not forget Topher Grace as David Duke, the enigma of the film: a prim-and-proper gentleman, a thin facade masking the pure evil lurking underneath. Other role players are solid as well; every member of the KKK was believable and scary, and some even showed moments of depth to their characters, despite having little to go on from the script in terms of character growth.

Conclusion

Once again, we have a film with a brilliant setup but less-than-ideal execution. BlacKkKlansman could have been a gripping, sharp, nuanced look at raced relations and instead plays as a thinly-veiled social statement dressed up with the trappings of character and plot development. I have nothing but respect for Spike Lee; he is a maverick, making powerful statements through the medium of cinema, something very few people are in a position to do. But with this film, I feel the desired message superseded the script, and sacrifices were made to cohesion in order to fit what Mr. Lee wanted to say about America. That is his right as the filmmaker; I can’t take that away from him. I disagree with many of the choices, but I know why he made them.

I would probably give this film a mediocre grade, mainly on craftsmanship issues, if I gave it a grade at all. But I’m not going to. Because this film was not meant for me. It’s meant for a narrow subsection of people who subscribe to a moral absolutist view of the world which I do not share. I prefer when films celebrate the nuance and relativity in human interaction, but my preference does not matter here, and that’s fine. And to be clear, I am not a white supremacist by any stretch of the imagination, and I largely agree with Spike Lee’s sentiments on this matter. I simply believe film should be about character growth and multi-dimensionality, and there was little of that to be found.

TL;DR: The film as a craft has problems. The film as an art form embraces those problems in favor of its messages. And because the two are intrinsically-linked, I can’t in good conscience attempt to separate them, so I can’t grade the film accurately.

VERDICT: (abstain)

What did you think of this Spike Lee joint? Please feel free to roast me in the comments for my undoubtedly-controversial opinions. I’ll be happy to respond to constructive criticism and consider alternate arguments on the matter, because contrary to popular rhetoric these days, I still believe humans have the capacity to learn and change.

-Austin Daniel

All image rights belong to Focus Features.

16 thoughts on ““BlacKkKlansman” Review & Analysis”