Todd Phillips’ Joker is by far the most polarizing film of awards season, with some (the public) calling it a masterpiece and others (the Film Twitter bubble) calling it vapid trash. The majority of criticism has been leveled against the film’s screenplay, with many pointing to the on-the-nose dialogue and vague social messaging as signs of weakness. This, unfortunately, is the result of non-screenwriters not realizing what makes a strong script. It isn’t all about dialogue and thematic content: it’s about structure, character development, and staying a step ahead of the audience, all of which Phillips does exceptionally well. Today I’m going to dive deeper into the film’s screenplay and defend the film’s awards season success.

Leaning into Audience Foreknowledge

Despite the studio’s attempts to present the film as a singular, “original” story for greater awards prestige, this is undoubtedly a comic book origin story of a familiar character we all know. The debate still rages on whether or not the film’s quality is impacted if the Batman mythology was removed completely from the film, or if an audience member had never heard of these characters before. (Surely it wouldn’t have made a billion dollars, but that’s beside the point). Honestly, it doesn’t really matter, because we live in a world where the Joker DID exist beforehand and the audience DOES know what kind of person he will become. How, then, does a screenwriter craft a narrative that is still ahead of the audience when they already know the ending?

It’s a unique problem to have, but Phillips solves it by leaning into this public-knowledge ending for natural foreboding. Tarantino did the same thing in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood: we all know (or suspect) that the film ends with the Manson murders, so he creates characters who are blissfully unaware of the horror at their doorstep. When we already know that Arthur Fleck eventually becomes Joker, the key is in making the audience feel smart for knowing things about our characters that they do not know themselves. When Arthur is given a gun for “protection”, we know that he is the last person on Earth who should be trusted with one. When a group of drunken businessmen harrasses Arthur on the train, we know that they are messing with the wrong person and Arthur is capable of great evil. These little moments are enhanced by audience foreknowledge, rather than hindered by an inability to mask the film’s intentions. Phillips knows that is a fruitless exercise, so he doesn’t even try.

The other thing this approach allows Phillips to do is litter the film with red flags. When we already know Arthur will become the Joker, we’re watching the film for signs of what’s to come, of what led to his downfall. And many of these signs are highly public: the harrassment by a street gang in broad daylight, the disturbing comedy set, the mockery on live TV. Any one of these incidents in isolation doesn’t necessarily make a murderer, but when Arthur sees setback after setback we have to wonder: how did nobody else see this coming?? That doesn’t work as well if we don’t know Arthur will have a downfall, because we aren’t necessarily looking for those clues in the moment. Phillips doesn’t try to hide the ending: he crafts his story around it, acknowledging that we all know it’s coming and invites us to look at other aspects of the storytelling to derive meaning.

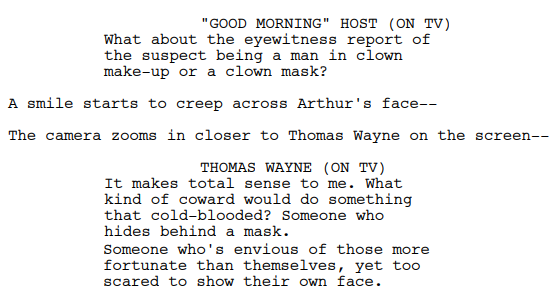

This concept doesn’t only apply to Arthur, but to several other Batman characters who make appearances in the film. The scene in which Arthur visits Wayne Manor and speaks to Thomas’s son Bruce would be out of place in a non-comic book story, but fans of the story will recognize the added nuance to their infamous relationship when Arthur is fashioned as an outsider literally separated by a fence from the more privileged youngster. Thomas Wayne himself is fashioned as a villain, which to my knowledge no Batman story has done before, and any savvy viewer will know that he winds up dead eventually, orphaning young Bruce. There’s an inherent irony to the fact that his values set him apart from the man his son will become, especially his stance on vigilantes:

The audience, knowing how crucial of a concept a mask is to Batman’s identity, can’t help but chuckle at the irony of this comment. Again, the line works fine on its own for Arthur’s story, but the double meaning is a clever way to wink at the audience and reward them for knowing things about the story outside of the immediate narrative.

Another way Phillips stays ahead of his audience is by creating subplots designed to keep them guessing. A good technique to subvert expectations when an audience comes in with foreknowledge of the character is to provide information that contradicts what they thought they knew. For instance, I don’t know if I’ve ever seen a Batman-Joker relationship told in a way that paints Bruce Wayne as the silver-spoon trust fund kid and Joker as the scrappy underdog who hates him for all the things he has without ever working hard for them. The idea that they might be brothers just further amplifies their divide: they are cut from the same cloth, but grew up to become diametric opposites thanks entirely to their vastly-different upbringings. The “illegitimate son” subplot also works when you take out the context of the Batman story, because it gives Arthur a glimmer of hope that perhaps he has a ticket out of his current predicament. If his rich father only knew that he existed, that would pull him and his mother out of this hole!

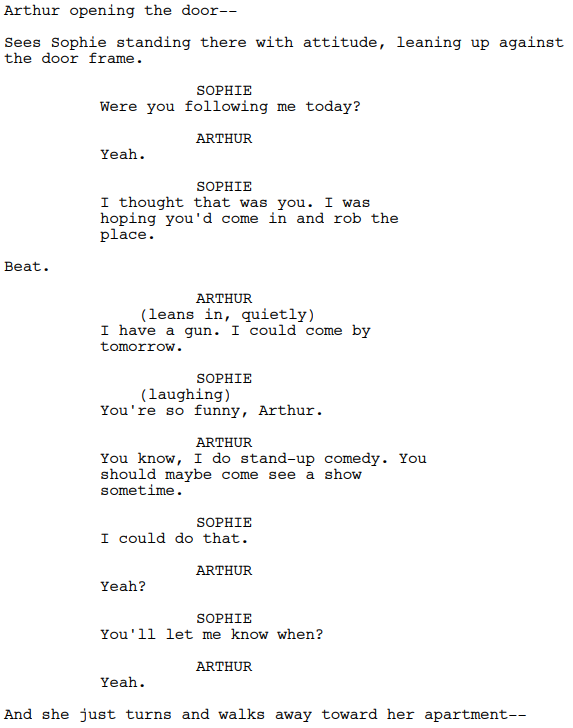

Similarly, the subplot with Sophie is a clever “gotcha” moment that allows the filmmakers to pull the wool over the audience’s eyes when they weren’t expecting it. The reveal that their relationship was all in Arthur’s head is a fantastic twist that wouldn’t work nearly as well if not for careful planning and seed-planting throughout the first two-thirds of the film. We’ve already established that Arthur has imaginary conversations and encounters, as when we see him “appear” in Murray Franklin’s audience and get called up on stage. We’ve already established that he has a tendency to stalk people he’s interested in, as when he confronts Thomas Wayne at the charity event. I was struck on second watch by how “obvious” the twist should’ve been, just based on dialogue exchanges like this one:

A good twist should not only shock and surprise the audience, but also make perfect sense in hindsight. And the Sophie reveal does, because the added context allows us to look back and realize that exchanges like the one here are projections from Arthur’s mind for how he expects such a conversation to go. What we dismissed earlier as mere awkwardness of two strangers having a meet-cute was in fact the deranged hallucinations of a madman. For it to work on both levels without the audience noticing is a spectacular feat, and the mark of strong screenwriting.

The Invisible Man

A key part of Arthur’s character development is in how he feels “invisible” – not only that society has left him destitute, but seems to have forgotten about his existence entirely. Phillips knows that in order to give Arthur a meaningful progression from mild-mannered citizen to full-blown psychopath, he can’t just be crazy for crazy’s sake…he has to want something. And all Arthur wants is to be acknowledged, to be SEEN, and he quickly realizes that the only way to do so is through public acts of violence.

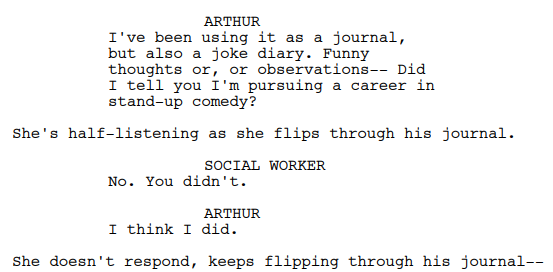

We see this just two minutes into the film, as Arthur visits with his social worker:

It becomes clear over the course of the scene that this social worker isn’t really listening to Arthur’s answers, just going through the checklist and saying what she’s supposed to say. And it’s implied that Arthur is testing her: making little offbeat comments, using her assignments for other purposes, even a literal cry for help (“I just hope my death makes more cents than my life”) to see if she’ll notice. And she doesn’t…just confirming his suspicions that nobody cares about him.

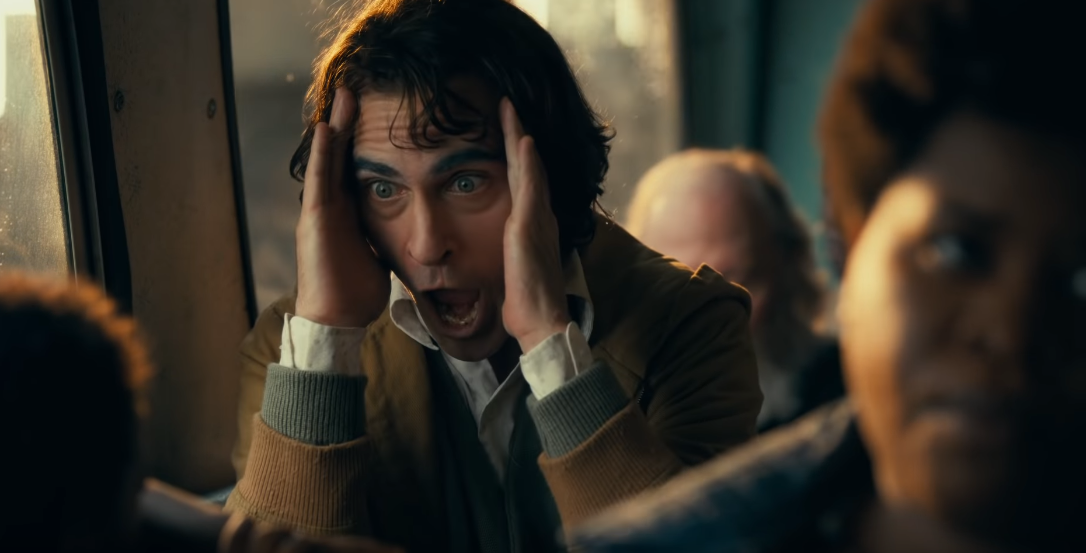

Things change dramatically for Arthur after he kills the three businessmen on the subway. Not only does this awaken something lying dormant within him, he finally feels as though the world is noticing his existence. The prevalence of television in the lives of people like Arthur means that acknowledging the murders on the medium is akin to Arthur getting his first taste of fame:

Not only does Arthur feel seen for the first time, he also feels understood thanks to the response by the city protestors. He’s been conditioned to believe that his negative thoughts about society are unique to him, that he is alone in his frustrations with the system. Now for the first time he feels that there are others out there like him: sick and tired of the poor treatment of the lower class and the mentally-unstable. His bolstered confidence comes through in his next (and final) meeting with the social worker:

But as Arthur soon learns, not all attention is positive. When the Murray Franklin show picks up the footage of his bombed comedy set, his elation at being “seen” by society is quickly replaced with horror:

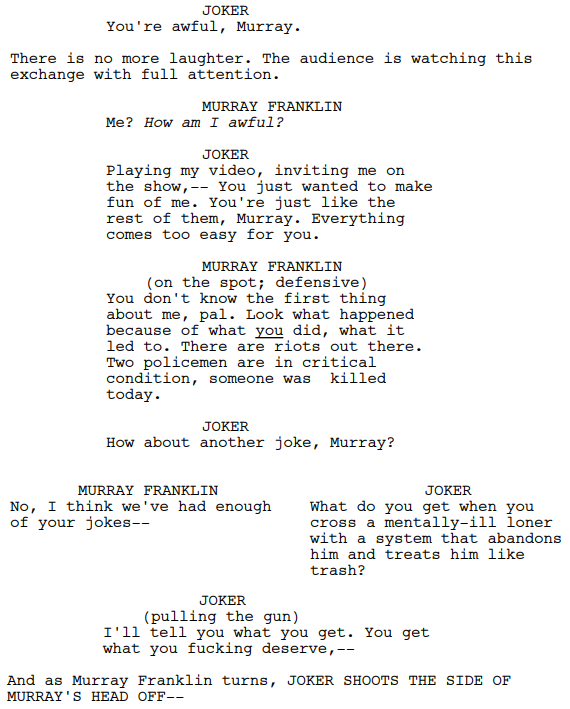

It’s at this point that Arthur realizes that he is not truly invisible…worse, he is a pawn used for people more well-off than himself to laugh at and feel better about themselves. To add salt to the wound, he gets an invite to appear on the show soon after – only now he recognizes that they want him to show up so they can make fun of him some more. So when he does appear on the show, he takes it as an opportunity not only to make his voice heard and his troubles known (as he’d always wanted to do), but also to call out the people who laugh at his misfortune.

I will say that I agree this is the most on-the-nose exchange in the film and the criticism surrounding the choice of dialogue is valid. However, that doesn’t mean that the emotional impact of the moment is not earned! The key lies in Arthur’s “I hope my death makes more cents than my life” mantra. Thanks to Murray, Arthur realizes that his death won’t change anything – in fact, it would only be exploited for the benefit of others, the people who prey on the weak and use their misfortune to feel better about themselves. The misspelled “cents” (sense) could be seen as a cutesy accidental typo, but perhaps it is an intentional reflection on the profiteering of misery. Arthur believes that in order to instigate REAL change, he has to upend society’s view of men like Murray Franklin and point out his hypocrisy. Otherwise, his death will be just as meaningless as his life and the cycle of resentment will continue. He’ll be just as invisible in death as he was in life.

Just Smile!

Mental illness plays an important role in the plot of Joker…not only in how it can lead to alienation and disenfranchisement from society, but in how there is an unspoken expectation for those suffering from it to shut up about it. As Arthur writes in his journal in a poignant (if a tad on-the-nose) snippet, “The worst part of having a mental illness is people expect you to behave like you don’t.” This mentality fits perfectly with the Joker character, who wears makeup so that he always appears smiling. And as we learn throughout this film, that idea came from Arthur’s feeling of always needing to smile to pretend like nothing is wrong – even when his life is a living hell.

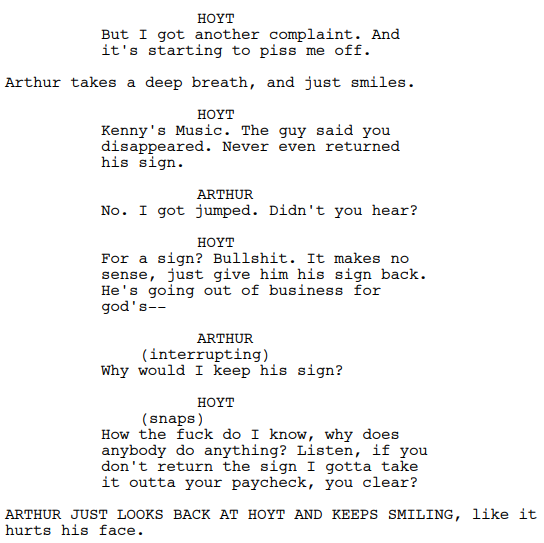

In situations where Arthur is frustrated and/or powerless, his only possible recourse is to smile and pretend it’s fine:

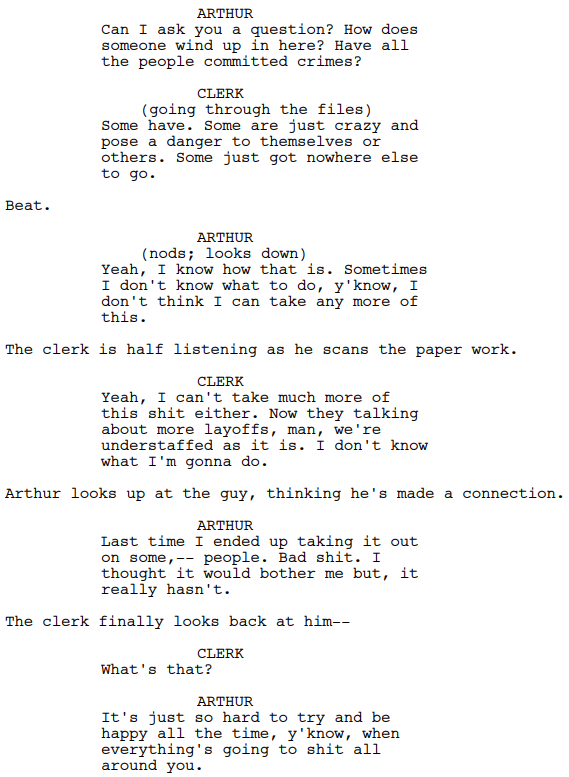

Arthur seems to believe that in order to function in society, one is obliged to hide their true emotions and always put on a front of happiness to avoid ostracization. In fact, he seems to yearn for a simpler time, when he didn’t have to worry about putting up fronts and could just express how he’s really feeling without fear of the judgment of others. He muses on this fact as he visits Arkham Asylum to retrieve his mother’s case file, a place he was once interred in and perhaps longs to return to:

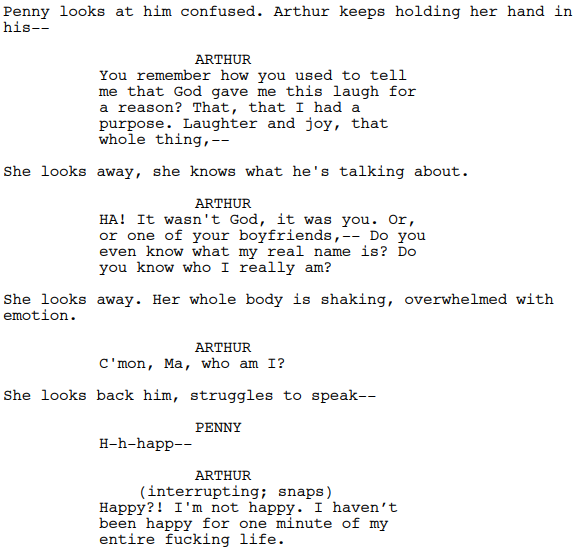

As we come to learn, Arthur has practiced this technique all his life, largely thanks to his mother. She calls him “Happy” and often remarks on what a good, cheerful boy he’s always been. But it turns out this was an illusion as well – Arthur’s coping mechanism as he is repeatedly beaten and mistreated by his mother and her abusive boyfriend at the time. His “condition” of laughing in uncomfortable situations came not from a genetic disorder as we thought, but from the severe abuse he suffered and his attempts to laugh through the pain.

The genius of this film is in how Todd Phillips and Scott Silver completely rethink the “why” behind the character of the Joker: why the laugh? Why the comedic demeanor? Rather than just make Arthur a generic clown and call it a day, they really dig deep into the specific conditions that might cause somebody to develop a laughing disorder to cope with severe pain and trauma. They reimagine the character as someone who went through traumatic experiences that they couldn’t properly address, experiences that many others have at the bottom rung of the societal ladder. They draw specific attention to the painted smile of a clown face mask and question whether the actor behind that mask is really as happy as he projects, or if he’s just putting on a good show to stay alive, to convince himself that things aren’t as bad as they seem.

Conclusion

Joker is a beguiling look at the dregs of society: the people passed over and forgotten by the capitalism machine, unable to rise up and make something of themselves. It depicts a dystopian society in which the poor are not only outcast and mistreated, but openly mocked and even blamed for their lot in life. It’s a bleak portrait of the world, one where we understand the conditions that can cause a mentally-unstable man like Arthur Fleck to transform into the monster we all know today. And yet there is a glimmer of hope in Arthur’s story, a suggestion that if things had turned out just slightly differently – if someone had taken notice, if someone had reached out to him in his time of need – maybe it wouldn’t have turned out as bad. We come out sympathizing with Arthur’s plight while disagreeing with his actions, leaving us with a desire to treat one another a little better and hopefully prevent such a monster from emerging again. With our own society threatening to deteriorate as it does in Gotham, hopefully we realize the value in supporting the mentally-ill and the less-fortunate, lest such unrest begin to fester and bubble to the surface in such a violent manner as Arthur’s.

What did you think of Joker? Is it a fair assessment of how someone in Arthur’s shoes might react to severe poverty and distress? Does it both honor the source material and blaze its own trail? Is Arthur’s anger justified?

My awards season coverage continues soon as the 92nd Academy Awards draw nearer! I will be posting my Official Predictions soon before the ceremony, as well as more script analyses like this one for films like Marriage Story and Jojo Rabbit! Hope to see you again soon.

-Austin Daniel

All image rights and script excerpts belong to Warner Bros. Pictures.