Bong Joon-ho’s master work of a film Parasite (2019) took the Academy Awards by storm this year, nabbing four Oscars including Best Picture. And while I am absolutely thrilled that the Academy rewarded the best film of the year, I feel that we are only just beginning to scratch the surface of all the film is trying to say. This movie is far more than meets the eye: it is a multi-layered look at modern society and the rich vs. poor dynamic that does not trivialize or generalize its subject matter. It challenges the viewer to look at the situation from multiple perspectives and consider the at-times-conflicting viewpoints of each character. Today I will be digging deeper into the film’s Oscar-winning screenplay to try and unravel the carefully-constructed web Bong spins for our viewing pleasure. **SPOILERS AHEAD!**

Crossing the Line

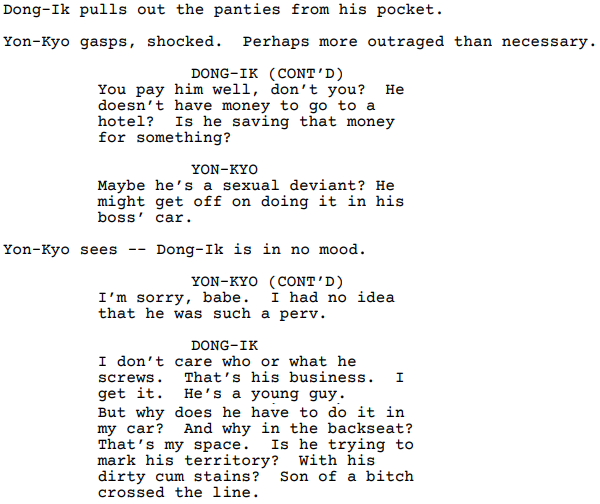

Bong specifically draws attention to the divide between the rich and the poor by imagining an invisible “line” that separates them, one that the poor dare not cross. The rich characters – particularly the father – often discuss this concept casually, as though to cross that line and assume equality with those above you is a cardinal sin. He first draws attention to it with his wife, as they discuss suspicions that their driver has had sex in his boss’s car:

It’s important to note that Mr. Park has no real gripe with the driver for his skills or conduct. In fact, he doesn’t even appear put-off by the guy’s sexual deviancy – more than willing to overlook the younger man’s personal life! No, the thing that peeves him is the idea that the driver would think himself noble enough to use his rich boss’s car for his own carnal pleasures. It’s like a middle finger to Mr. Park’s status, implying that the poorer worker has somehow usurped the established order and disrespected the power arrangement they had prior.

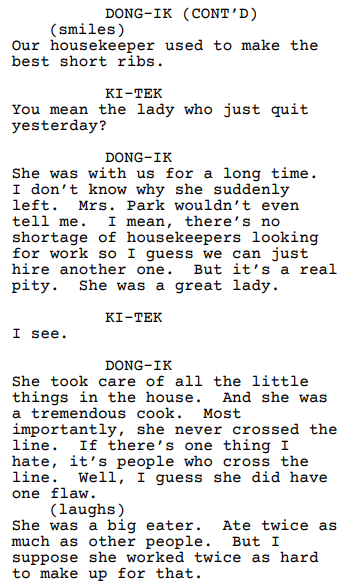

Now to be fair, having sex in your boss’s car is still pretty scummy so I can see audience members overlooking the deeper implications of the situation. But Bong continues to hammer home the concept of this “line” to be sure the audience recognizes how important it is to the Park family. Another instance occurs as Mr. Park discusses his ex-housekeeper with his new driver, Ki-taek:

Again, nothing but great things to say about her as an employee. Hard worker, good cook, great family friend. But the thing that’s more important than anything else – even questionable eating habits – is not crossing that line. The message is clear: if you want to work for the Park family, you can be freaky in bed and eat like a pig all you like, so long as you know your place in the pecking order.

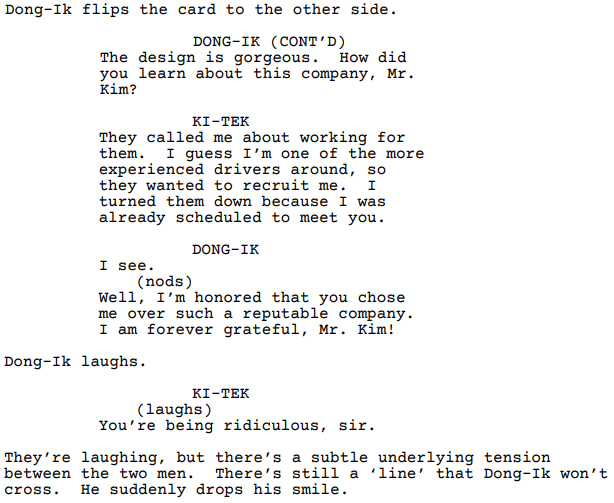

But this “line” goes both ways. Just as Mr. Park expects his employees to stay on their side of the line (distant reverence), he himself will never cross that line and accept his workers as anything more than that:

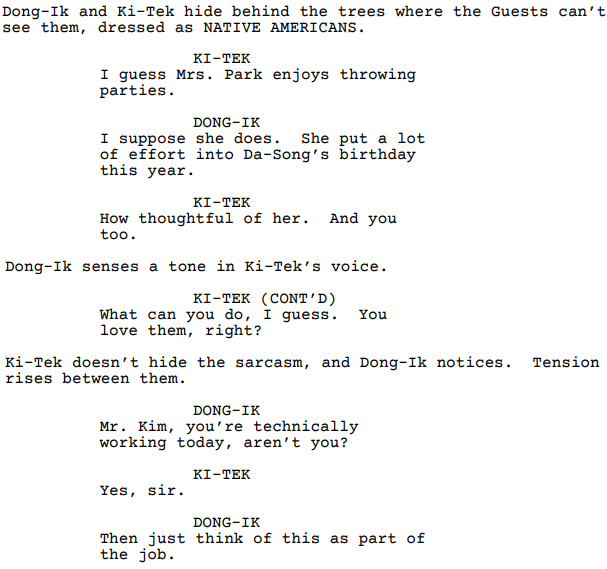

It’s clear that Ki-taek is buttering his boss up here and opening the door towards genuine friendship. But Mr. Park will never allow that to happen – he keeps his guard up, even as he praises Ki-taek and jokes around with him, he knows they can never be friends. That power dynamic must always be firmly in place, and any time Ki-taek attempts to become more than that, Mr. Park is quick to tell him off about it:

Part of the key to understanding Ki-taek’s terrible decision at the end of the film is in how he (and others) are treated by the rich family. While it may seem that they get the upper hand over the Parks, the Parks are still the ones in control at all times. And if at any point they feel threatened – that the line is being crossed – they quickly snuff any hope the Kims have of making their acquaintance on a personal level.

Stockholm Syndrome

An amateur might craft this film in such a way that the poor characters loathe the rich people lording over them. Instead, Bong depicts the opposite: instead of resenting the Parks for their opulence and ignorance, the Kims revel in siphoning off their wealth and accept the meager scraps they receive with gratitude. They are not evil, after all…at worst they are ignorant and gullible, but nonetheless good-natured and benevolent. In fact, this gratitude even manifests itself as worship at times, as though the poor come to actually RESPECT the rich for their meager financial offerings!

Perhaps no one is guiltier of this than Ki-taek. He actually mistakes the Park family’s pleasant demeanor as legitimate kindness – a sentiment his wife is quick to correct:

But Ki-taek is not the only person who shares this sentiment. Once we meet Moon-gwang and her husband living in the basement, we realize that they are much more advanced in their reverence for the Park family. And when they attempt to blackmail the Kims with the incriminating video, Ki-taek reasons with them by appealing to their reverence for the Park family:

It’s notable that he does not appeal to logic or reason (“We’ll all go to jail”), but to emotion, banking on the fact that they share his desire to please the Parks at all costs. He’s less concerned with losing his job than with upsetting the Parks, as though he has grown fond of them and would hate to see them disappointed! But Moon-gwang apparently has no interest in this, perhaps since she was fired from her job and has lost her respect for the Parks. On the other hand, her husband is still a devoted servant to the benevolent Mr. Park:

It’s also noteworthy that once Kun-sae escapes the basement and goes on his killing rampage, his targets are not the wealthy Park family – rather, he goes after the Kims, whom he now blames for all the troubles in his life. Even though his poor circumstances are entirely a result of the stratification of society and the terrible influence of money on the class system, he continues to point blame at the Kims who had little to do with his lot in life. Bong argues that the conversation surrounding income inequality has stalled because poor people have turned on one another and continue to blame each other for all the problems in society, instead of together looking upwards towards the REAL problem: those at the top who siphon off all the resources for themselves.

Sticks and Stones

From beginning to end almost without reprieve, the Kim family endures hardship after hardship, injustice after injustice. They are undeniably at the bottom of the totem pole in society, and they have grown accustomed to this fact by the time we meet them. While the film has an atypical story structure, there is a clear character arc for the Kim family patriarch, Ki-taek, which speaks volumes about how the poor have compartmentalized their trauma and learned to accept mistreatment – even if they secretly want to lash out and make their displeasure known to the world.

When we first meet Ki-taek, he is used to being belittled and has apparently hardened himself to mistreatment. Even in his own family – the quintessential place a man ought to feel in control – he accepts torment without question:

Immediately this sets off alarm bells in the audience. How is he so at peace with his shitty lot in life? Why does this guy not stand up for himself? Well as it turns out, he does – sort of. When his wife again negs him as they drink in the empty Kim household, he suddenly snaps:

It’s as if, for a fleeting moment, Ki-taek lets his inner rage explode before receding back into his defensive shell. This comes at the midpoint of the film, just in time for us to realize he’s not actually quite as mild-mannered as he seems: he harbors a deep-seated resentment for the notion that he is powerless and small in life.

The concept of “crossing the line” also reappears in the narrative late in the film, as Ki-taek hides with his children under the table after the Parks suddenly return home. They are forced to silently hide and listen as Mr. and Mrs. Park discuss Ki-taek’s performance as a driver thus far:

Again, Ki-taek betrays no emotion at this verbal beatdown he’s enduring – this reminder that he’s a nobody, a cretin of society. He may not show it, but context clues now tell us that he’s furious at his lot in life and is trying to train himself not to care. But he can’t keep up the charade forever. His final act of violence may come as a shock upon first watch, but in hindsight it makes perfect sense as a buildup of all the pent-up aggression he’s tried to keep inside all along:

This was no random act of violence. It was an awakening of something lying dormant within Ki-taek from the beginning: frustration with his (and other poor people’s) inability to be seen as human beings. We may not be meant to agree with his sudden outburst of anger at the Park family, but we definitely sympathize with and understand his plight. He has repressed this emotion for so long that it’s no wonder a man like that could snap and commit the ultimate crime. And no, I don’t mean murder – but crossing the line and usurping the power dynamic.

The Best-Laid Plans

Another major theme within the film is the concept of “having a plan”, or a lack thereof. While Ki-taek has already accepted his fate, his children – particularly son Ki-woo – still cling to the hope of a better life beyond their current circumstances. Ki-woo undergoes a journey of his own, one in which he desperately seeks to ingratiate himself with the rich and elevate himself to their level, only to suffer “imposter syndrome” and doubt his credibility as a member of the cultural elite.

At the beginning of the film, his father encourages his optimism and his efforts to get himself out of his current predicament:

“Man with a plan” is an innocuous-sounding statement of encouragement, but as we’ll later learn, Ki-taek has long abandoned the notion of making plans. His son is none the wiser, pressing on with his grand schemes and ambitions to pull his family out of poverty. He even uses his childhood friend Min-hyuk as a form of inspiration, modeling himself after his more affluent friend and trying to raise himself to that level of respect.

As the grand scheme to swindle the Parks unfolds, the Kim family comes to look to Ki-woo for guidance rather than Ki-taek (who shirks his responsibilities as the plan-maker of the group). Hell, even we come to believe that his plans can actually work after they successfully infiltrate the Park family! But no plan can go off truly without a hitch, and Ki-woo’s reliance on adhering to plans comes back to bite him when the former housekeeper returns to throw a wrinkle in them:

For the first time, Ki-woo realizes that even the best-laid plans can go awry when you’re as desperate as his family is. The events of the second and third act are entirely thanks to his own ignorance (willful or otherwise) to the way things truly are, and his efforts to join a world he has no part in partaking in.

While he has been largely distant and supportive for much of the film, in the third act Ki-taek finally imparts some of his life “wisdom” onto his son. After allowing his offspring to run free and let his imagination take him places, he lays the hammer down and makes sure his son understands the true nature of the world:

Despite his father’s clear pessimism, Ki-woo continues on his fruitless quest to fix the situation. It’s a heartbreaking bit of irony for us to watch as Ki-taek’s son dedicates himself to this task that we know is impossible. Bong even gives us a glimmer of hope – the tiniest taste that something good might finally happen to this family – only to pull the rug out from under us with the harsh reality of poverty in the 21st century.

Ki-woo’s relentless optimism that he can get his father out of this situation is a sad reflection of the lower class’s futile attempts to climb out of poverty. We have come to understand the father Ki-taek’s philosophy of having no plan at all, because at least then nothing can go wrong. He professes the virtues of setting one’s sights and ambitions low so as not to disappoint oneself, which is all that will happen should the poor attempt to improve their situation. And we know that Ki-woo’s plan can never work, despite the final montage giving us a small glimpse of hope that he could succeed in this endeavor. But if the events of the plot preceding it are any indication, this plan too will fail and his father will be doomed to live out his days in that basement as the housekeeper’s husband did before him.

Conclusion

There is so much more I could talk about with this film, largely to do with the film’s use of visual language – the native-American symbolism reflecting the Parks’ ignorance to its history, the use of food as a symbol for the patriarchy, the verticality of the set design to reflect the stratification of wealth, and much more. The amount of detail that Bong Joon-ho has put into his film is truly mind-boggling, and I imagine I will STILL be noticing new subtle details on my fifth rewatch and beyond. This is the kind of movie that will be dissected and analyzed for decades to come.

I do fear that we run the risk of misunderstanding Bong Joon-ho’s intended messaging with this film with a surface-level assumption that it is a critique of only the upper class. It criticizes not only the rich but the poor in the ongoing battle against income inequality, arguing that all the current efforts to rectify the situation are futile. He highlights the effective way in which the ruling class has turned the lower caste against itself, with infighting and petty disputes distracting from the REAL issue. However, he also does NOT posit that killing the rich is any more effective than killing the poor – it only reaffirms to society that the poor deserve to be where they are and further hinders progress. It’s a pessimistic outlook on life with little in the way of solutions, but Bong does advance the conversation by pointing out the follies of the fight in its current form and advocating that the disenfranchised make peace and band together in the fight against systemic oppression.

All image rights and script excerpts used courtesy of Neon and CJ Entertainment.

Thanks for reading! In the spirit of the Academy Awards, I will also be analyzing the other screenplay winner of the night: Taika Waititi’s Jojo Rabbit! In the meantime, head over to the home page for more film analysis and awards season recaps, including my upcoming column ranking every Best Picture winner ever! And don’t forget to check out my Letterboxd page for my up-to-date thoughts on each film I watch! Hope to see you again soon.

-Austin Daniel